Many years ago, when Walter O. Evans served in the Navy, he met a young lady at a party and asked her out on a date. She suggested a visit to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. "I'd never been to an art museum before," says Evans, now a retired general surgeon. "So I went to the library and read about the artists we'd see. And I told her about Monet, and how he had gone blind late in life, and Degas, who had lived in New Orleans."

"Ices 1" by Jacob Lawrence |

Before long, he caught the collecting bug, with what was at the time an unusual focus. "Dr. Walter Evans is absolutely one of the pioneer collectors of African-American art," says New York art dealer Michael Rosenfeld, who has long specialized in the field. "And he has collected in an encyclopedic manner, spanning the 19th and 20th centuries."

Evans now owns works by virtually every important black artist up to and including Modernism icons Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Archibald Motley, Robert Scott Duncanson, Mary Edmonia Lewis, Henry Tanner, Beauford Delaney, Alma Thomas, Norman Lewis, Benny Andrews, and Aaron Douglas. His 2005 gift of more than 60 artworks to the Savannah College of Art and Design barely put a dent in his trove, which numbers in the hundreds.

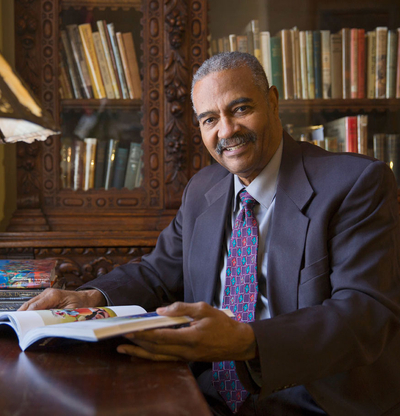

Walter O. Evans |

But if Evans is a hoarder, he is also a sharer. Because art changed his life, and kindled his interest in history as well, he decided in 1991 to put a selection of his treasures into an exhibition called "The Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art." Its tour, customized for each venue and managed by his wife, Linda, visited about 50 museums before ending in 2012.

Recently, Evans—who retired in 2001 at age 58 and moved back to his birthplace, Savannah—talked about his passion for art and history. At his brick antebellum house in the historic district, he appeared elegant but understated, dressed in earthy olives and browns (a sign of his relaxed self-confidence was on display on his feet, which were clad only in a pair of brown socks). Though soft-spoken, he eagerly rose from his stuffed chair in the drawing room to illustrate his points: for example, how Bearden, whose colorful gouache of a man and woman, Presage, hangs over the fireplace, had folded the paper and painted a landscape on the other side.

Surrounded by paintings on every wall in every room and up the staircases, plus sculptures in every available spot, Evans says he has no trouble deciding what to hang in his home, which is outfitted in dark woods, Oriental rugs, flowing curtains, and other Victorian furnishings. "The museums decide," he says. "Museums are always borrowing things." He notes that a painting called The Plotters normally hangs on the front wall, but it had been loaned to the traveling exhibition "Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist."

Evans says he did so well as a collector because he had little competition. He frequented the few galleries that sold African-American art 30 or more years ago, bid at auction, and sometimes, as with Bearden, bought directly from the artists, many of whom he befriended. "All of them were bargains when you consider today's prices," he muses. Now, he says, he probably couldn't afford the vivid street scene by Lawrence, which depicts a vendor scooping ices for children and hangs by Evans's fireplace.

Evans calls himself an opportunistic collector, but says, "I knew which artists I wanted to get, and what I bought had to do with financial ability—I may not have had the funds." Occasionally, he made a mistake. In the '80s, he was advised to buy portraits by Joshua Johnson, a biracial painter who made a living painting wealthy Baltimoreans and who died around 1824.

"I said I didn't want that, that I wanted my daughters to come into the house and see works with African-American images in them," Evans explains. Regret arrived a year later in 1988, when the Whitney Museum of American Art sold Johnson's Little Girl in Pink With a Goblet Filled With Strawberries for $660,000, nearly 15 times the previous record for a Johnson painting.

"Girl Seated" by Margaret Burroughs |

Even then, recognition was not forthcoming. Evans related the story of Rhode Island artist Edward Bannister, who entered his landscape Under the Oaks in the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. It won the medal, but when Bannister tried to claim his prize, the astonished judges attempted to reverse their decision. Only after other artists—white artists—threatened to withdraw their own works did the judges relent. Evans has a Bannister hanging in his dining room.

Evans loves talking about his treasures. In the hallway, he pulls down Horace Pippin's Victory Garden to show the labels on the back that reveal where it has been exhibited: the Museum of Modern Art, the Phillips Collection, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and the Brandywine museum. "In the '70s, when I started, Pippin was the only African-American artist whose works were going for six figures," he says.

That has obviously changed; so many more people desire this art now. Historical works are less available, and while Evans says he likes the works of some contemporary black artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, he has mostly stopped buying art. But what about those manuscripts that he's collected along with the many works of art? Yes, that story continues.