Philadelphia

When, in 1910, Mexicans began to revolt against the long, autocratic regime of President Porfirio Díaz, they also ignited a revolution in Mexican art. As rebels fought to create a more equitable, democratic system, artists struggled to forge an identity that embraced both Mexico's culture and international modernism, often supported by government patronage.

"The Offering" |

Impressively, the exhibition comprises sculpture, photography, prints and graphics as well as paintings. Even huge, unmovable murals—still the most remarkable aspect of Mexican modernism—are present via three digital displays. The best one projects, in rotating panels, the courtyard façade of Mexico City's Ministry of Public Education, which Rivera had covered with "Ballad of the Agricultural Revolution" (1926-27) and "Ballad of the Proletarian Revolution" (1928-29). An interactive display explains his powerful scenes and some of their characters (such as Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller in "Wall Street Banquet"). It's an excellent use of technology in an art museum.

Organized chronologically, the exhibition begins with several paintings that reflect Europe's artistic traditions and, at times, add subtle Mexican references. Perhaps the most beautiful one, Saturnino Herrán's "The Offering" (1913), shows an indigenous family in a canoe full of marigolds, for use in Day of the Dead traditions. Starkly illustrating the evolution to come, Siqueiros—later the angriest, most incendiary of the muralists—starts out here, at about 17, with "Peasants" (c. 1913), a pastoral landscape. Kahlo, age 19, makes her debut with "Self-Portrait in Velvet" (1926), a demure, elegant picture inspired by Botticelli, with none of the angst of her later images.

Rivera, meanwhile, had been in Europe, producing Cubist still lifes, landscapes and portraits; yet by 1915, with national identity much on artists' minds, he paints "Portrait of Martín Luis Guzmán" with a serape blanket and other Mexican symbols. Going political, Francisco Goitia, a staff artist in Pancho Villa's army, creates a bleak "Zacatecas Landscape With Hanged Men I" (c. 1914).

"Lion and Horse" |

But other artists, believing in art for art's sake, remained keyed to more international trends and less political subjects. One example, of many, is Julio Castellanos, whose "Three Nudes (Breakfast)," from 1930, depicts Mexican women in the neoclassical style many European artists, including Picasso, had tried.

In ensuing years, many Mexican artists continued to engage with international art, bringing Surrealism, Expressionism and other forms south, and foreign interest in their work flourished, spreading Mexican sensibilities north.

Orozco, for one, moves to New York and is soon hired by Dartmouth College to produce a mural (the second digital display here). He delivers "The Epic of American Civilization" (1932-34), boldly contrasting Mexico's ancient myth of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl with a dark view of the Americas after the Spanish conquest. Alfredo Ramos Martínez goes to Los Angeles, painting works like "Compassion (Man in Bondage)" (1940) on the newsprint pages of the Los Angeles Times. Numerous Americans and Europeans, from Edward Weston and Tina Modotti to Elizabeth Catlett, travel to Mexico; their works are integrated into the show, too.

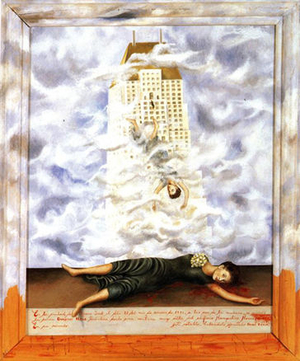

"The Suicide of Dorothy Hale" |

It is hard not to notice, though, that many of the best pieces are by the five giants, who together created about 40% of the works on view. Paradoxically, then, an exhibition that rightly aims to expand knowledge of Mexican modernists simultaneously reinforces the dominance of a few.

Yet that fact should not take anything away from this bracing show. When "Paint the Revolution" was announced, the museum described it with a favorite, clichéd adjective among museums—calling it a "landmark" exhibition. Sometimes, that's a real stretch. Not here.