Entering the Narga Selassie church in northwest Ethiopia is a bit jarring. The circular stone church, built in the mid-1700s, resembles the spare, thatched-roof homes many Ethiopians inhabit even today. It sits on grass worn by pilgrims' feet on an island in Lake Tana, the country's largest lake. It looks neglected.

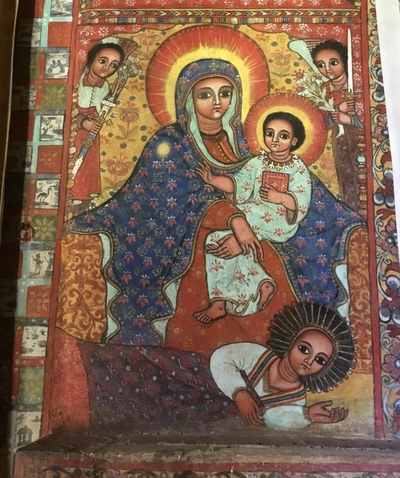

Mary and Child |

Ethiopia has been a Christian nation since the mid-fourth century, and its churches are famous—with the monolithic, rock-hewn churches in Lalibela that date to the 12th century being extraordinary engineering and architectural feats. Narga Selassie is the best example of a different species of Ethiopian church, built centuries later on the peninsulas and islands of Lake Tana—with its reputation centered on its artistic splendor.

An 18th-century queen named Mentewab built Narga Selassie, which is dedicated to the Holy Trinity, in gratitude to God. Raised on a plinth slightly above ground level, it consists of three parts. At the center sits a square inner sanctuary, or maqdas, reserved for priests, where is kept the tabot, or replica of the stone tablets citing the 10 Commandments that were given by God to Moses. The sanctuary is surrounded by a circular ambulatory, intended for use during services by those receiving communion. It, in turn, is encircled by an arched, open-air portico.

West door, detail, with St. Michael |

The west side is the loveliest, probably because in Ethiopian tradition priests enter the church from the west, while other men use the north side and women the south. Here, the tripartite door shows, in the center panel, Moses leading the Jews from the desert and the Pharaoh and his men drowning, among other themes. Archangels, keeping watch with intent black eyes, their Afro hair surrounded by golden halos, dominate the side panels: On the left, St. Michael brandishes two swords; on the right, recalling a local legend, St. Raphael harpoons a big fish that was harassing a local town.

The archangels wear embroidered and brocaded garments, with wide pants unlike those worn by Ethiopians—betraying foreign influence. During the 15th century, two Venetian painters had spent time in Ethiopia's royal courts and the Jesuits had arrived, bringing with them religious paintings, prints and illustrated books, including some from Mughal India—all of which crept into the style of these paintings. The archangels' ornate garb and slippers—whose toes are pointed outward—borrow from Mughal miniatures. The increasingly modeled faces and the growing realism depart from the flatness of the art that came before, which was more Byzantine in style. (Christianity arrived in Ethiopia from Syria, scholars believe.)

An upper wall |

These are original works by anonymous painters, but they follow a type seen all over Ethiopia's churches. The round faces have the same stylized eyes. Most people face forward, or nearly so—anyone portrayed in profile is evil, as Herod is on the south wall as he orders the slaughter of the Holy Innocents. The charming cherubs that dot many paintings are just heads with wings. Presiding, on the west wall's drum, is the Holy Trinity as three elderly men, a common Ethiopian way of depicting this mystery of faith.

They amaze. When I visited Narga Selassie last fall, a group of college students, all dressed respectfully in white robes, was there, having ridden a crowded ferry for three hours across Lake Tana to reach the church. Indelible in my memory is the sight of one young woman standing just outside the south entrance, her hands outstretched from her waist, in prayer. But even as she and others worshiped, a few could not resist interrupting their pilgrimage to take photographs.