New York

Don't be fooled by "Dance in Tehuantepec" (1928), Diego Rivera's colorful, seductive painting of a folk custom that opens "Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945" at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

It beckons visitors into a gallery of artworks that, following the end of the bloody Mexican revolution in 1920, romanticized the country's indigenous peoples and their culture. Americans like Paul Strand and Edward Weston, whose visits to Mexico are well documented, followed their lead, and their works here seem familiar. Other pieces, by less-known artists from north of the Rio Grande, such as "Women With Cactus" (1928) by Everett Gee Jackson and "Women of Oaxaca" (1927) by Henrietta Shore, are vibrant and charming, but seem only to imitate Mexican artists.

"Dance in Tehuantepec" |

Soon enough, each one came to work in the U.S., affecting the imagery, style, process and purpose of art here more deeply and broadly than previously acknowledged, "Vida Americana" argues. It aims to add a chapter to American art history between the early 20th century prominence of European-inspired modernism and the postwar dominance of Abstract Expressionism. It shows that these Mexicans, and others, influenced artists ranging from Jacob Lawrence to Charles White and even, fleetingly, Isamu Noguchi and Will Barnet, who is best known for his flat, figurative domestic scenes.

"Zapatistas" |

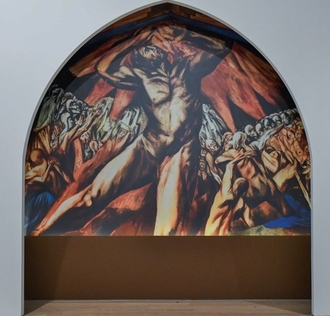

"Man, Controller of the Universe" |

At one end of the spectrum is Jackson Pollock, who saw Orozco's works while just a high schooler and later participated in Siqueiros's "Experimental Workshop." He took up their expressive brushwork and discordant themes in works like "Untitled (Naked Man with Knife)" (1938-40) and "The Flame" (1934-38), and helped lay the groundwork for his still-to-come, rhythmic drip paintings with works like "Composition With Flames" (1936).

"Prometheus" |

In between are artists including Philip Guston, whose dense, dystopian "Bombardment" (1937-38) captures the nightmare wreaked on humans by a bomb explosion, a reference to Spanish Civil War atrocities. Bendor Mark's "Execution" (1940) also portrays man's brutality, taking up some of the thick brushstrokes used by Siqueiros in "Revolutionary March" and Orozco in "The Unemployed" (c. 1929). Among many strong images, two others stand out, both empathetic comments on suffering and labor: Eitarō Ishigaki's "The Bonus March" (1932) and Marion Greenwood's "Construction Worker" (1940).

And many other artists owe something else to the Mexicans, according to the catalog. Inspired by Mexican government programs for artists, the American artist George Biddle in 1933 wrote to his friend Franklin Delano Roosevelt, telling him that the Mexicans had created their murals only because they were paid wages to express their ideas in government buildings. Roosevelt's administration soon started several programs that hired artists for thousands of public art projects. But unless you habituate post offices, colleges or small museums, you will be unfamiliar with many splendid narrative works (shown here in sketches, studies, cartoons) by artists like William Gropper, Mitchell Siporin, Hale Woodruff, Henry Bernstein, Michael Lenson, Fletcher Martin and Anton Refregier.

You might ask, who are all these artists?

"Construction Worker" |

Still, to draw on the pop song, changes in latitudes do change attitudes—and after "Vida Americana" the history of American art doesn't remain quite the same.