Every now and then, the art world is rocked by a sensational story about art conservation. There are good ones, like the recent unveiling of Jan Van Eyck's Mystic Lamb in the Ghent Altarpiece, freed from 16th-century overpainting that had obscured his human-like face. And there are bad ones, like the century-old Spanish fresco of Christ that was ruined by an overzealous amateur restorer in 2012. No wonder museums have increasingly built special exhibitions around these fascinating stories or included conservation as part of their shows.

Tut's tomb |

If you know nothing about the subject, one place to start is the website of the Dallas Museum of Art, which has posted five introductory videos—each less than 2 minutes—beginning with "What Is Art Conservation?" Watch as former chief conservator Mark Leonard explains the essential task of conservators—which is to understand what the artist did and wanted to say, then reverse any human or other interventions that have changed that.

Mr. Leonard relates fundamental principles—for example, that conservation should be reversible, because interventions will age differently from the original materials. "Whenever we change the way a work of art looks, we alter its meaning," he says.

"Conservation at the Harvard Art Museums"—16 videos on Vimeo—also delves into the basics. Scraping away paint layers added to an 18th-century American sculpture, senior conservator Tony Sigel addresses the challenge of how far to go. Pausing to assess, he says, "If conservators or restorers restore every single last paint loss, it can really kill an object." In another Harvard video, then conservation fellow Andrea von Hedenström removes varnish from a Monet painting with a fine brush and sponge and takes up the same issue: "It's always a decision: Is the treatment more dangerous to the paintings? And then of course we cannot go any further." (Spoiler alert: She left some varnish on the painting.)

Adam, restored |

These granular stories are often engrossing. Consider the tale of Tullio Lombardo's "Adam" (c. 1490-95), a life-size marble statue owned by the Metropolitan Museum. In 2002, his pedestal collapsed, sending him crashing to the ground, dissolved into 20 major fragments and hundreds of smaller pieces. In an eight-minute video on the Met's website, the museum's conservators relate how they documented everything, as "you would in a crime scene," recording where the pieces fell on a grid. Confronting this 3-D jigsaw puzzle, they studied it, devised a reassembly plan, tested various adhesives and pinning materials for their stress capacity. They even broke another statue to "plan our armature." Only in 2010 did they begin assembling Adam, finishing in 2014.

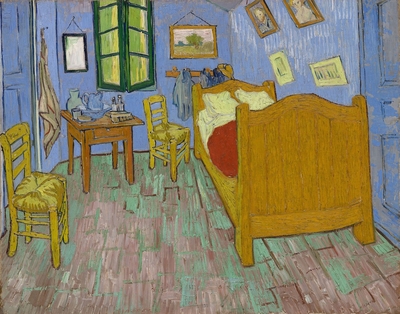

The conservator as detective surfaces, too, on the Art Institute of Chicago's YouTube channel in "Under Cover: The Science of Van Gogh's Bedrooms," made for a 2016 exhibition uniting all three versions of the scene. Scientists like Francesca Casadio use cutting-edge tools, like a macro-X-ray fluorescence scanner, "to penetrate below the surface of the works to discover things our eyes cannot see." Among the revelations: The bedroom walls of the Chicago painting, now light blue, were originally purple. The museum enlisted color scientists, who developed a complex algorithm to create a digital visualization that allows viewers to see what Van Gogh actually painted.

Also from the Art Institute, "A Thousand and One Swabs: The Transformation of 'Paris Street; Rainy Day,'" about its famous Caillebotte painting, uses speeded-up video as a conservator removes varnish, revealing brighter flesh tones and an earring, thought to be a pearl, as a diamond.

van Gogh's Bedroom |

The Whitney interviewed many artists about their methods and materials to inform future conservation work—an effort now incorporated into the Artists Documentation Program, which is run in collaboration with the Menil Collection. Currently, you can find informative videos about the conservation of recent art on the YouTube channels of the Museum of Modern Art (Matisse's discolored "Swimming Pool") and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Chris Burden's complex kinetic sculpture "Metropolis II," which requires 35 hours per week by four conservators to maintain and repair it). The work of a conservator never ends.