In what seems like alchemy, three pieces of art, made at different times in the eighth and ninth centuries in disparate parts of Europe, were turned into an amalgam that is considered one of the greatest treasures of the Morgan Library and Museum: the dazzling Lindau Gospels.

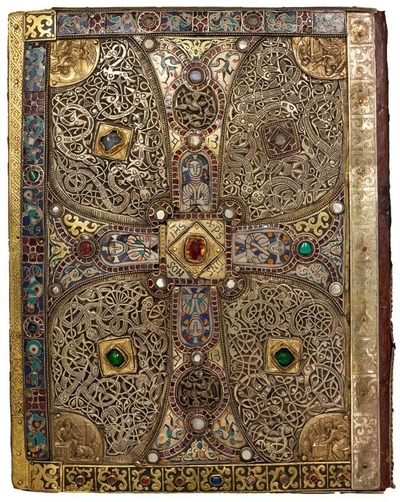

Front cover |

All these centuries later, it is a rare surviving example of a well-preserved, superbly crafted medieval treasure-bound book of Scripture, one of just two important specimens sourced to the empire created by Charlemagne. Adding even more allure, at some point the inside covers of the book were lined in a precious commodity—patterned silk fabrics from Byzantium (date unknown) in the front, and from the Near East, possibly Syria (eight or ninth century), in the back.

At the Morgan, the Lindau Gospels occupy a vitrine in the library, their ornate front cover shimmering in the subdued lighting. Yet despite the gleam of gold and of more than 300 sapphires, pearls, emeralds, amethysts and garnets, it is the low-relief, repoussé image of Christ on the cross that stands out—literally and figuratively. He is rendered, in an impeccably draped loincloth, as Christ Triumphant over sin and death. The blood dripping from his wounds forms little grape bunches, a reference to the wine transformed into his blood in the Holy Eucharist. Above him is an inscription reading, in Latin, "Here is the King of the Jews." And above that are circular personifications of the sun and the moon in mourning.

Back cover |

The large, domed jewel clusters at the center of each of quadrant, called "bosses," are both stunning and functional: They protect the reliefs from damage when the book is open. Like the whole cover, each one is nearly symmetrical, with an oval sapphire surrounded by round and rectangular gems, aloft on tiny feet. This three-dimensionality continues throughout the cover, and the predominance of gold suggests that the artist intended the cover to convey meaning: It is "a vision of heavenly Jerusalem as it's described in the book of Revelation," said Joshua O'Driscoll, assistant curator of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts at the Morgan, thus "transforming the crucifixion into a celestial vision of heaven."

This cover, probably created around 870-880 in eastern France in the workshop of Charles the Bald, a grandson of Charlemagne, is totally different from the back cover, which was made in the late 700s, probably near Salzburg, Austria. Seemingly more restrained, made of silver gilt, enamel and far fewer jewels (about 30), its design is more intricate. This medley of many metalwork techniques, including pierced relief and cloisonné, with designs influenced by Viking, Mediterranean and Irish styles, may well have been the front cover of another Gospel book.

Although you cannot see this cover at the Morgan, the museum has made digital images of both covers and all the manuscript pages available on its website.

On this back cover, Christ appears in four half-length images, each set in a red enamel niche in the arms of a flared cross. A topaz, in a diamond-shaped square, adorns the cross's rectangular center, which is anchored at each of its four corners by a pearl. Inside the square center, split into four segments, an inscription reads "Jesus Christ Our Lord" in Latin. At the cover's corners are depictions of the four evangelists. The four quadrants, each with a boss, are a chaotic mass of intertwined serpents, birds and quadrupeds—a mix repeated in the borders and mentioned in Genesis, Mr. O'Driscoll said. They suggest the moment of creation and allude to the Gospels as the source of eternal life. The repeated use of the number four refers to the four cardinal directions, the four seasons, the four classical elements and, of course, the four canonical Gospels.

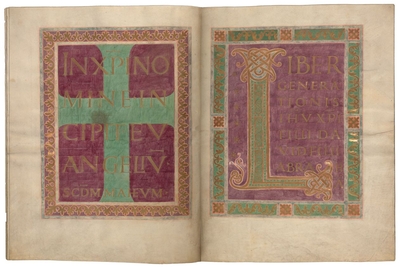

The manuscript |

As a 11-minute video narrated by the Morgan's director, Colin B. Bailey, also on the museum's website, relates, J. Pierpont Morgan purchased the Lindau Gospels in 1901. This survivor from the early Middle Ages captivated him, and in the eyes of the world turned him into a serious collector of manuscripts. Later, Morgan gave away thousands of artworks to other museums. But he kept the Gospels, and his other manuscripts, as core holdings of the institution bearing his name.