Williamstown, Mass.

Hmmm: an artist almost no one in the U.S. has heard of, not even art scholars. Born in the 19th century. Norwegian. Male. At first glance, these are not exactly the ingredients for an alluring special exhibition nowadays, especially for a public emerging from a long pandemic and yearning for some excitement.

"By the Open Door" |

Fortunately, the name of the artist in question is easy to pronounce, because after seeing " Nikolai Astrup : Visions of Norway" at the Clark Art Institute, visitors will want to remember it. Astrup (1880-1928) created brilliantly colored paintings and woodcuts inspired by his love for nature, frequently spiced with allusions to Norwegian folklore. Viscerally beguiling, they are even more intriguing to those who look closely at Astrup's world.

The son of a Lutheran pastor, Astrup was born in remote western Norway. He trained in Oslo (then called Kristiania), spent time touring art museums in Germany, studied at art schools in Paris, and went home, returning to Norway's Jølster region, about 160 miles north-northeast of Bergen. He struggled with health issues, self-doubt and financial problems, but took part in various exhibitions in Norway (and occasionally elsewhere). He kept up with developments in modern art, perusing journals, traveling abroad, and exchanging letters with other cultural figures. Today, he is one of Norway's best-loved artists: Most of his works reside in museums or private collections there, and most literature about him is in Norwegian.

That began to change about a decade ago, some years after Norway's Savings Bank Foundation DNB acquired a collection of Astrup's work, lent them to a Bergen museum, and began to finance research and English-language publications about him. In 2016, he was given an exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, curated by British art historian MaryAnne Stevens, that traveled to museums in Emden, Germany, and in Oslo. When, in 2017, Kathleen Morris, a curator at the Clark, and Alexis Goodin, a research associate, saw her speak at a London symposium, they were instantly taken by his art and the trio soon began work on the current show (which the foundation has helped sponsor).

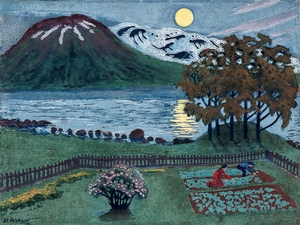

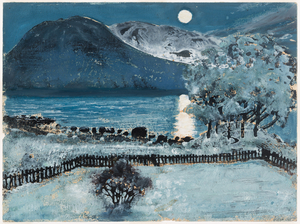

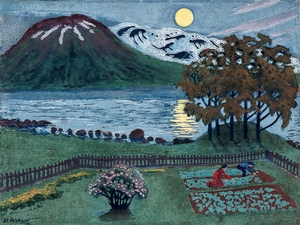

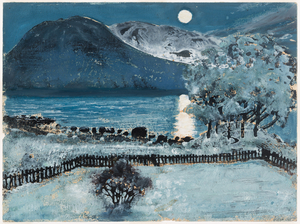

The Moon in May |

Visitors will also see his appeal immediately, in the first gallery, which is filled with paintings of Astrup's formative surroundings—the scenery, farm and parsonage that served as raw material for his entire career. Surprisingly, it's awash in green. Instead of focusing on the long snowy winters and glacial terrain, Astrup lovingly presents Norway as a verdant place. In simple, sometimes naïve, images, he creates a sense of longing for times past. "The Shady Side of the Jølster Parsonage" (before 1908), for instance, portrays a blond girl staring into a window of Astrup's cherished childhood home, which had been deemed uninhabitable. "By the Open Door" (before 1911) shows two women looking out from their deep-hued home to a picket-fenced garden, wetted by rain that heightens its emerald tones.

The Moon in May |

In a beautiful painting titled "A Clear Night in June" (1905-07), Astrup captures the moment the sun sets behind the mountains, its glow strong enough to illuminate a row of farmhouses at the foothill and, more so, the marshy green meadow, dotted with yellow marigolds, that occupies half the painting. Astrup would return to this scene several times, including in his woodblock prints.

That is the territory the exhibition next explores. Working with limited imagery, Astrup in 1904 extended his imaginative range by turning to the flat, simplified forms of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which he had seen on his European travels. He developed his own techniques, carving a block for each color—as many as 10 for one image—and hand-printing them with slow-drying oil paints that caused him to wait months to finish one work. Often, he added color or detail by hand, reinforcing the uniqueness of each print. With such subtle adjustments, he would change the season or the mood, as demonstrated here in four impressions of "The Moon in May" (c. 1908).

Foxgloves (1909) |

An even better illustration of Astrup's creativity comes in an enchanting series called "Foxgloves," first painted in 1909. With white birch trees and pink foxgloves on the right, and birds, cows and a stream reaching toward a blue-sky horizon on the left, it's a dreamy mélange of soft hues. Years later (c. 1915-20), he created six "Foxgloves" woodblock prints, two of which are on view. In them, he flips the image, placing the birches and the flowers on the left, and on the right he adds two girls, dressed in red, engaged in the age-old practice of picking berries. He also varies the intensity of the colors, sharpens the profile of background mountains, thickens the tree canopy, moves the stream and makes other changes. Finally, Astrup paints another version (c.1920) whose composition matches his prints.

Midsummer Eve Bonfire |

Astrup created still lifes and domestic scenes, too, some of which are among the more than 85 works on view—notably the ambitious "Birthday in the Parsonage Garden" (1911-27). But the essence of Astrup resides in the final gallery, which contains his folkloric Midsummer Eve bonfire paintings. With their bold colors, dancing flames and sensual brushwork, they light up the exhibition the way the fires lit up Norwegian nights. In several, a lone female figure stands apart, watching the merriment from afar. The image hearkens back to Astrup's upbringing, when his strict father prevented him from attending these mystic festivals because of their pagan roots. Metaphorically, it also suggests Astrup's distance from the established art world—a gap that, one hopes, is about to close.