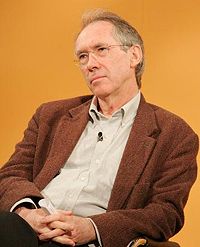

For a man whose many novels have explored violence, obsession, sexual deviance and devastating loss, Ian McEwan turns out to be a pleasant, low-key fellow off the page. At least that's how he appeared on a recent visit to Manhattan. Dressed in a casual charcoal-gray jacket and rumpled slacks, he slumps a bit in his hotel-room chair as he responds to questions, answering each one reflectively, frequently quoting the likes of Seneca, Henry James and Wallace Stevens. As he finishes his thoughts, his voice tails off until it's almost inaudible. He waits patiently for the next query, sometimes glancing away.

Perhaps Mr. McEwan has mellowed. Since "Atonement," his historical novel published here in 2002, his works have been far less dark. Or perhaps, considering that a teacher once described him as "hopelessly shy," he has actually grown in exuberance, however limited it remains.

Either way, Mr. McEwan has reason to be in a great mood. At age 59, he ranks among the greatest writers of his generation, probably the best of the British contenders. He was a heavy favorite this year for the Booker Prize for Fiction for "On Chesil Beach," a slim novel that quickly climbed the best-seller lists last summer, and narrowly missed repeating his win in 1998 for "Amsterdam." "Atonement," commonly considered to be his masterpiece, is now a movie starring Keira Knightley and James MacAvoy. He recently completed the libretto for an opera by his friend Michael Berkeley called "For You," which centers on a 60-year-old composer who's fading both professionally and sexually. Mr. McEwan's angular face and wispy hair are familiar to readers, though he says "the rare people who come up to me are very tentative and extraordinarily polite, and they say they just want to tell me what a wonderful book I've written and they're gone."

Ian McEwan |

Unlike many literary authors who shudder at the damage moviemakers can do to a book, Mr. McEwan has made his peace with film. "Atonement," he says, is "visually splendid," "well-cast and beautifully performed," and "in no way an affront to the book." But, he adds, "this is a very interior novel, and that's one thing movies can't do."

Mr. McEwan has written screenplays, including one for "The Innocent." But films are controlled by the director, not the author, he says, so he'd rather spend the three years it takes to do a movie writing a novel. For "Atonement," he took the title of executive producer, had "endless meetings" with scriptwriter Christopher Hampton, director Joe Wright and producer Tim Bevan -- and made a few visits to the set, especially for the World War II scenes at Dunkirk. Then he went back to his work.

About which, let's clear up a few things: He dislikes the "Ian MacAbre" tag bestowed on him for his early works. "It went on for long after it was relevant," he feels, "and the awful thing was that each writer thought he had discovered it." He concedes that "it was reasonably well-earned at the time. Those stories were very dark, and I'm not sure where they came from." Then he continues: "They were a young man's extravagant pessimism, which can be delicious. The world is so fresh and solid, and you think it could use a bit of shaking up. I'm part of the generation that grew up in prosperity. Our parents were desperate for ordinary lives because they'd seen the chaos, whereas we saw nothing but advances in personal wealth and freedom, so we could imagine the worst things."

In any case, his writing had the desired effect: "It was a young man's insistence on being noticed," he says.

But soon critics started using another bit of somewhat irritating shorthand to describe Mr. McEwan's widely varied writing: the notion that each of his works hinges on a single moment that changes everything. "Atonement," for example, pivots on a young girl's misperception of and subsequent testimony about a crime. "Saturday," his post-9/11 novel, turns on the accidental run-in between a neurosurgeon and a thug. "On Chesil Beach" revolves around a dysfunctional honeymoon night. "All it really says is that in my novels something happens," Mr. McEwan tells me. "It got said, and then it got into the loop. It's a truism, really. It's true of any novel."

Mr. McEwan believes in the power of literature to wreak change and cites as one example not only the life of Salman Rushdie but also the violence and deaths his works spawned. "And I remember going to Eastern Europe during communism, how important literature was in people's lives and to the regimes to suppress it."

On a lighter note, Mr. McEwan says that at one appearance in a Rome bookshop he had four couples come up to him, with their seven children in tow, to say they'd met because of his books. "A guy on a bus would see a girl reading 'Enduring Love' and go up to her," he says. "Great, I thought, I'm providing brilliant pickup lines."

Though Mr. McEwan declined to do an American book tour for "On Chesil Beach" (visiting only New York) and is doing little to promote the "Atonement" movie, he accepts many public demands on his time. On this trip to the U.S., he visited Princeton University for a public reading, participated in the New Yorker Festival, and taped an interview for Borders Books. "I won't do this all the time," he says. "I find it impossible to simultaneously occupy public space and private space -- it's fine to talk and I like to give readings, and the students at Princeton more than engaged me. But being in public is contrary to the currents necessary to generate writing. I do feel desperate after a while, desperate to reclaim some silent core to myself."

No wonder, given the past few years. Mr. McEwan's messy divorce in 1995 from his first wife, which caused continued custody problems and led to a court-ordered gag order on her, made headlines for years. In 2005, belittling his reputation for meticulous research, London's Evening Standard noted a "howler" of a mistake in "Saturday": It mentioned a Mercedes S500 with a fourth gear, but the car's strictly an automatic. "Then the tabloids erected a feeble case of plagiarism," Mr. McEwan continues -- charging him with borrowing too heavily for "Atonement" from a wartime memoir he had already noted in his acknowledgments. Early this year, when word broke that he had an unknown brother, who was given up for adoption six years before Mr. McEwan was born, the headlines blared again.

So far, the celebrity culture hasn't had much effect on his writing -- "though one could write a comic novel about it," he says. "It's so fitful and omnivorous; one minute it's on you, and then it's gone and it's on someone else." And it does bring readers.

Mr. McEwan believes that "more literary fiction is being read now than it used to be" -- even if mainstream culture is "stupid and gross and hysterical." When he started, people thought literary fiction was for a distinct minority of people, he says, rather like "trout-fishing or barn-raising." He credits the Booker Prize as one factor that changed that.

Mr. McEwan proclaims himself to be a "great lover" of American culture. "But I only take away little bits of it," he says. "I'm not great on pop culture." Rather, in tune with his lifelong love of music -- he plays the flute -- when he visits the U.S. he frequently spends his evenings at jazz or blues joints; his taste runs to John Coltrane, Miles Davis, bebop, and music through the early '60s, including rock 'n' roll.

For all his range, Mr. McEwan has never set a novel in the U.S. "I might do it one day," he muses, probably set around New York. "There's something positive that appeals to me about American culture," he says, launching into a story about a visit he and his wife made last November, on Veteran's Day, to Revolutionary War sites in Lexington and Concord with John Updike and his wife. "There were hundreds, if not thousands, of people about, and I noticed how many Muslims there were," he says. "That's something we've not achieved in Britain or the rest of Europe. I tip my hat to that part of American culture."