Williamstown, Mass.

In the first half of the 20th century, when modernism was changing the very nature of art, two rich brothers, heirs to the Singer sewing machine fortune, were buying up paintings like the hedge-fund managers of today. One, the business executive, was dutiful, public-spirited, an adventurous but strategic art collector who wanted to shape public collections. The other, the boulevardier, was self-centered, private, a conservative but voracious collector who bought for personal pleasure. After an early closeness, they argued, came to fisticuffs and never again spoke.

Their tastes diverged as well, and even when they collected in the same areas, they had different views: The first looked forward, seeing Impressionism and Post-Impressionism as the harbingers of the new; the second looked back, seeing late-19th-century Impressionist and French academic works as the culmination of painting.

How ironic that the first, Stephen C. Clark, a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art; a benefactor of them, the Yale University Art Gallery, the Addison Gallery in Andover, Mass., and many other museums; a founder of several cultural institutions in Cooperstown, N.Y., including the National Baseball Hall of Fame; and a card-carrying member of the New York City power elite, has been largely forgotten. And the second, Robert Sterling Clark, is well-known as the founder of the museum bearing his name in Williamstown, Mass., that is a must-visit fixture on the summer art circuit.

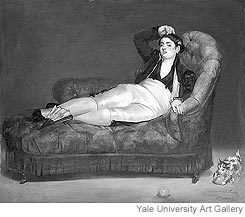

Manet's "Young Woman Reclining in a Spanish Costume" is typical of the bold works purchased by Stephen Clark |

The result is an exhibition that not only is a pleasure to view but also affords a wealth of learning without being pedantic. It's actively engaging, too: It gives museumgoers a chance to guess "who bought it?" and to decide "who has the better eye?" In an age when so many museums have gone astray with shows to attract "new audiences," this triple feat is to the Clark's great credit.

The game is kicked off right away, when viewers face two of the loveliest paintings in the show: "Onions," a luminescent still life by Renoir purchased by Sterling, and "Still Life With Apples and Pears," a strong Cézanne that Stephen bought and bequeathed to the Met. Onions, here sketchy and golden, have never looked better; Cézanne's apples and pears are bold and beautiful in a strong composition. Game -- fairly even.

In the following galleries, whenever the exhibition pits one brother's choice against the other's, the contest shifts back and forth, as viewers confront a series of works that offer natural, sometimes uncanny, comparisons. Both brothers bought self-portraits by Degas, for example. Both bought still lifes by Renoir. Stephen's -- "Still Life With Peaches" from 1881 -- boasts a better composition, more so because Sterling's choice -- "Apples in a Dish" from 1883 -- seems a tad stilted.

There are less obvious comparisons, too. Renoir's "Sleeping Girl With a Cat" (Sterling) is juxtaposed with Manet's "Young Woman Reclining in Spanish Costume" (Stephen). Each shows a girl, a cat, and a similar furniture leg. The Manet is the audacious work -- the girl stares straight at the viewer and, although she is clothed, the work is compositionally similar to the artist's shocking "Olympia," painted several months later. And there is Sargent's formal, posed and polished portrait of his teacher, Carolus-Duran (Sterling), right next to Eakins's realistic, narrative portrait, "Dr. Agnew" (Stephen), which shows the doctor at work, scalpel in hand.

Both brothers liked works by Winslow Homer, and the exhibition features several. Here, their differences narrow. You would need to know the brothers very well to guess which purchased "Weaning the Calf," showing two white boys watching a black youth handle the animal, and which bought "Two Guides," a picture of two hardy men out for a hike in the Adirondacks, both dated 1875.

Sterling's choices are generally, but not always, more conventionally beautiful, more intimate, and more seductive, often with visible, sensuous brush strokes. Stephen's picks are generally, but not always, bolder, more forceful, and more original. (He bought "Weaning the Calf," whose narrative suggests race and class issues, and seems more complicated than that of "Two Guides.")

So today Stephen, who kept the family fortune growing and resented having less time to spend on collecting, is viewed as the better collector. Sterling, who made collecting a focal point of his life, sniggered at the very pictures that allowed Stephen to outdo him. "To think of these wretched Matisses, Gauguins, Cézanne bringing thousands and thousands of dollars!!!!" he wrote in 1934. Sterling actually considered buying works by Cézanne, the father of modern art, according to Michael Conforti, the Clark's director, but never did. "He was not a free painter," Mr. Conforti explained. "He did not have a lively brush."

Still, Sterling cannot, and should not, be dismissed. A self-taught connoisseur, he was a man who could in a single day buy a Renoir and a painting by Gérome, who was famed for his historic, often Orientalist works. He was a man who sought out works by Piero della Francesca and by Frederic Remington, by Monet and by Bouguereau, the academic painter who staunchly opposed the Impressionists. He collected in depth, and beyond paintings, amassing a vast trove of books, manuscripts, silver, ceramics and prints.

This exhibit, just over 70 pictures in all, would need many times the available space to show either brother's collection fully. By focusing on the decades when Modernism was budding, the Clark essentially makes Stephen outshine Sterling.

You can see that conclusively in the exhibition's final gallery, which showcases Stephen's modern masterpieces: van Gogh's "Night Café," three Cézanne, including "The Card Players," that are now in the Met's collection, plus Picassos, Matisses, Vuillards. Only one painting from Sterling's entire collection, Mr. Conforti said, would have fit in this room -- Toulouse-Lautrec's "Jane Avril."

Beyond its compare-and-contrast goals, this effort was conceived with another aim. Mr. Conforti wanted to place the Clark brothers, together, in the company of collectors like Duncan Phillips, Chester Dale, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and perhaps even Alfred Barnes as patrons who helped shape America's taste for Impressionist and Modern pictures. Much of the evidence is in the catalog, which lists all of Stephen's purchases and their current locations. The rest is in the Clark's permanent galleries. Mission accomplished.