New York — At 9:45 a.m. one recent Tuesday, the huge center stage of the Metropolitan Opera is a construction site. Carpenters, scenic artists, electricians and other back-of-house workers are moving around in somewhat organized chaos, putting together the set for Act III, Scene I of Wagner's "Götterdämmerung." The forest clearing, where the action takes place, is sitting, half-assembled, on a 60-foot-wide wagon, stage-left, not quite ready to be wheeled to center stage by electric motors. It's messy; it's noisy.

Stage-right, on another wagon -- basically a flatbed truck, minus the cabin -- stagehands are working on the hall of the Gibichungs, whose columns rise four stories into the stage's well, for Act III, Scene II. That, too, must be ready soon: It will be moved into the central spot when the forest-scene wagon exits, back to its home stage-left, in midrehearsal (but not before stagehands rush around turning up the pieces of tarp that hang over the wagon's edges, making sure they are not damaged).

Yet when Maestro James Levine walks down the aisle to his conductor's post at a few minutes before 11, the forest set is transformed. What was still a bit of a jumble 10 minutes before now looks spectacular. At its base, just below stage level, the Rhinemaidens who open the scene are ready to bobble up on cue. ("All right, ladies, stand by for the first up," says a stage manager named Theresa Ganley.)

The marvel of it is all the more striking when you understand what is happening.

"Götterdämmerung" isn't running tonight. It's just in staged rehearsal, starring Katarina Dalayman as Brünnhilde and Christian Franz as Siegfried, with complete sets and full orchestra. Last night, the Met had performed "Don Giovanni," an opera with 11 scenes; by 8 p.m., it'll be offering "Il Trovatore," a production that debuted in February and changes scenes, all built on a turntable, 12 times.

"Götterdämmerung" isn't running tonight. It's just in staged rehearsal, starring Katarina Dalayman as Brünnhilde and Christian Franz as Siegfried, with complete sets and full orchestra. Last night, the Met had performed "Don Giovanni," an opera with 11 scenes; by 8 p.m., it'll be offering "Il Trovatore," a production that debuted in February and changes scenes, all built on a turntable, 12 times.

Only in between, this morning and afternoon, is the company using the sets for Act III of "Götterdämmerung." They'll be gone before 4, so that the stage crew can put sets for "Il Trovatore" in place by 90 minutes before curtain, which is 8 p.m.

That's three changes of sets, for three different operas, in 24 hours. Some pieces are kept in-house on wagons or in storage areas; others are stored in New Jersey and transported to the Met by container truck.

If you have never understood why an old saying calls opera "the most expensive human endeavor, with the possible exception of war," a day at the Metropolitan Opera explains it. The divas, maestro, managers and orchestra are just part of the equation. So much else goes into the productions, made more complicated by the Met's tradition of staging operas in repertory. The Met is often a 24-hour operation. Make that a 24/6 operation, and occasionally 24/7.

In the past 24-hour cycle, the night gang had "struck" -- that is, broken down -- the "Don Giovanni" set, holding it in-house for its next performance, so that by 8 this morning, when the day crew arrived, it was gone. They set up "Götterdämmerung," and they'll take it down, allowing assembly of "Il Trovatore."

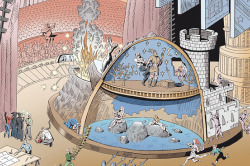

And in this highly complicated logistical puzzle, what's happening on the main stage -- which isn't a monolith, by the way, but rather a series of "lifts," each strip six- to eight-feet-wide, that rise and decline hydraulically, as needed, for effect -- is only a fraction of what's happening in the house. Elsewhere -- in halls, studios and an underground stage -- other rehearsals are taking place, though only a few use scenery and usually not much. Upstairs, in "shops" built around the stage well (which rises nine stories), employees are making costumes, wigs, scenery and other operatic necessities. And don't forget white-collar functions such as finance and marketing. Everyone hears what's happening on the main stage via a PA system, because everyone needs to know.

In the costume department, for example, workers -- 100 at season's height -- are making outfits for next season's eight new productions. They must also turn out replacements whenever there's a new cast member or a garment wears out. All told, that's about 1,000 new costumes each season.

It's a job that has grown more voluminous since General Manager Peter Gelb started high-definition simulcasts to theaters around the world. "We're looking at camera-worthiness now," says Lesley Weston, head of the costume shop. Like other shops at the Met, the costume department keeps "bibles" for each production. There's one for sketches and swatches, one for photos of finished costumes.

Next door, wig-stylist Tom Watson is using human hair to fashion a wig for Elina Garanca, who'll soon sing in "La Cenerentola." It's a revival, but again the fact that it's being simulcast on May 9, the last day of this season, means the wig, especially the netting that holds it in place, must be more subtle. The Met employs five wigmakers (vs. 15 at Covent Garden and 60 at the Salzburg Festival, Mr. Watson says).

The scenery shop is working on next season's new productions of "Carmen" and "Attila." Similar work is going on in the metal shop, the props shop and so on.

Back in the main arena, Mr. Levine kept the rehearsal going longer than the planned noon stop, not adjourning until 12:30 for a 40-minute lunch break. At 1:10 p.m., Mr. Levine is instructing orchestra and singers with comments like "please be sure during this passage that it gets softer and softer" and "the trumpets are a little harsh." Typically, I am told, Mr. Levine runs through the morning rehearsal without too many interruptions. But after lunch, he stops the music more often to make tweaks. Charmingly, he sometimes mimics the music to show, rather than tell, his musicians what he wants or doesn't want: "No, no, just be sure -- dubbah, dubbah -- we never do that."

"That's perfect now," he continues. "Yes, that's the music."

Others are fine-tuning as well. Electricians are making sure the lights are focused on the right place at the right time; that's done manually during the performances, not by computer. Carpenters have modified the below-stage area where the Rhinemaidens must move quite quickly through a narrow passage, with ups and downs, crouched. To make one portion of the way a little easier to traverse, they've placed a small wooden box.

Master electrician Paul Donahue is fixing the end-of-Valhalla fire, too. In this scene, Brünnhilde takes a butane torch, with a real flame, from the wall to light a funeral pyre. She douses it almost immediately in a fireproof crib; the pyre effect is achieved with two stage lights, a smoke gun, steam, explosion powder, a dimmer and a wooden cage no more than five feet wide. After seeing it this morning, "I wanted more pop," Mr. Donahue says. This afternoon, he added more powder and turned up the lights.

During both rehearsals and performances, members of the stage crew wait off-stage, in the wings or in nearby hallways, until they are needed. That can be during a scene, when they'll send a piece of scenery "flying" onto the stage. Or it can be between acts, when they'll change the sets completely. They take their cues from their department head or from stage managers, who make sure that everything proceeds at the planned moment.

Most productions have three stage managers; "Götterdämmerung" requires four, says Chief Stage Manager Thomas H. Connell III, because "so much is going on." The lifts are moving up and down; there are many singers and lots of scenery; and there's that fire to worry about. And the opera lasts six hours.

Mr. Connell is himself masterminding "Götterdämmerung." Sitting just off stage, he communicates with the stage managers -- they all move around -- via wireless headsets. He's also in touch with someone from lights, lifts and wagons, sets, and other relevant departments. Mr. Connell will give the master cue -- something like "Move, One, Go" -- and each department knows what that means for its own cues.

To keep apace, he watches a monitor of the stage, glances at the action and follows the score with the eraser end of a pencil so that he knows exactly where things are. Mr. Connell learned this opera a long time ago, he says, but whenever the Met adds to its repertoire, stage managers (the Met has six others) have to learn it, too. "We're absolutely interchangeable," he says.

The company has until 3 p.m. to get through this rehearsal -- or the evening performance could be in jeopardy.

"If we don't finish by 3 p.m., we stop," Mr. Connell tells me. "Immolation interrupted." But while we were talking, Mr. Levine has jumped ahead. On stage, up comes steam, someone calls for smoke, and the pyre "blazes." There's a pop, pop. Valhalla descends on those lifts. The Rhinemaidens' rock ascends, descends and ascends again, leaving them in possession of the Rhinegold, which they had at the beginning of Wagner's four-part "Der Rings des Nibelungen," three operas ago.

The rehearsal is finished by 2:57 p.m.

"That's excellent," proclaims Mr. Levine.

"Thanks to the crew and chorus," says Mr. Connell.

"Have a good rest of the day," Mr. Levine adds.

Soon everyone is gone but for the crew that swarms the stage to clear it completely, before setting up "Il Trovatore" (except for Valhalla, which unbeknownst to this evening's crowd, will hang above the rear-stage wagon during the performance).

Jerad Schomer, the technical assistant for "Il Trovatore," has taken over from Elizabeth Mills, who oversees technical matters for "Götterdämmerung." Mr. Schomer is in charge of about 100 workers, but everyone seems to know his or her job. They've already started assembling that critical turntable set on which the props will sit.

Compared to "Götterdämmerung," this job seems easy. But Mr. Schomer begs to differ. Yes, almost everything remains on the turntable throughout the opera -- there's little moving of things in and out from the wings -- but everything also depends on that turntable. If the center pivot isn't perfect, the motors won't work and the scenes won't rotate. Slowly, after putting the turntable grid in place, incorporating part of a wall, workers top it with another piece of wall, a fire pit and plywood painted to resemble rocks. The complete turntable takes three hours to assemble.

As this is happening, there's action going on behind the rear stage. Some men are unloading sets from containers on the dock. They're for "Das Rheingold," which is being performed in two days, but hasn't been staged in over three weeks.

And when "Il Trovatore" ends this particular evening, at about 11:15, this entire process goes into reverse, yet again. Less than 12 hours later, another rehearsal of "Götterdämmerung" begins at 11 a.m. sharp.