During much of his lifetime, Paul Cézanne was a rather solitary figure, aloof from the Impressionists he knew in Paris and, later, in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence, even more distant. Since his death in 1906, however, he has picked up a posse of followers that grows and grows. "Cézanne and American Modernism," at the Montclair Art Museum, amply demonstrates his defining influence on artists on these shores, adding new names to an already substantial list.

Five Apples, Paul Cezanne, Courtesy Montclair Museum of Art |

By zeroing in on American Modernists between 1907 and 1930, Montclair curator Gail Stavitsky and Katherine Rothkopf, her collaborator from the Baltimore Museum of Art, have provided a different visual experience. Philadelphia's exhibit had more stars, true. But the (mostly) lesser known 34 artists in this show offer fresh examples of a truth that has been universally acknowledged for decades.

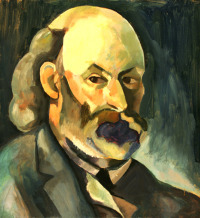

Portrait of Cezanne, Morgan Russell, Courtesy Montclair Art Museum |

Dasburg had traveled to Paris a few years earlier and, upon discovering Cézanne's work, divided his art into "before" and "after." Here his charming "Floral Still Life," from 1912, sharpens the angles on vibrant red flowers in a slightly off-kilter composition. His softer, earth-toned portrait "Judson Smith" (1923) also employs acute angles, flat planes and straight lines. By then, Dasburg was traveling to New Mexico, proselytizing for Cézanne and Cubism. Among his students was Nash, whose "Self-Portrait With Pipe," from 1928, comes straight from Cézanne's many man-with-pipe pictures, but Americanized, with a more casual pose and a striped shirt unlikely to be seen in Aix.

Likewise, it's a revelation to see photographers Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen here. The works by Strand, such as "Pears and Bowls" (1916), and Steichen, such as "Three Pears and an Apple" (1921), are particularly convincing. Choosing subjects Cézanne painted again and again, these photographers did not ape him; they imbibed his use of space and light to create their own style.

Those works all come near the end of the show, which follows a loosely chronological path. To begin, the curators display several black-and-white photographs of Cézanne paintings that were purchased in Paris by Max Weber in 1909. Weber intended them to guide his work upon his return to the U.S. But so intent on learning about Cézanne were Americans that these photos were exhibited in Stieglitz's gallery, 291, in 1910 and published in his Camera Work in 1913.

Nearby is a duet of paintings that encapsulates the show: In fact, Cézanne's "Five Apples," from 1877-78, morphs into Morgan Russell's "Three Apples," from 1910, on the catalog's cover. Russell saw "Five Apples" at the salon of Gertrude and Leo Stein; at Leo's urging, he borrowed it and never looked back. His works in Montclair closely follow, even copy, Cézanne—including a 1910 portrait that parrots Cézanne's "Self-Portrait, 1879-82" in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. Yet Russell went on to study with Matisse, to mature as an artist and, with Stanton MacDonald-Wright, to found synchromism, an abstract movement linking color and harmony.

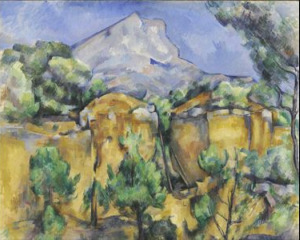

Elsewhere in the show, there are fewer direct pairings than could be seen in Philadelphia: Montclair, with no Cézannes of its own, was able to borrow just 18 of them, and they are used as centerpieces, surrounded by works they inspired.

Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen From Bibemus Quarry, Courtesy Montclair Art Museum |

For that is the test American Modernists had to ace: to pass through the Cézanne crucible and come out, not as imitators, but as something else. Many here do. Charles Demuth's lovely "Apples" watercolor may be an homage, but his "Housetops" and "Red Chimneys" situate distinctively American homes in a flat-planed background and stand on their own. Charles Sheeler's beautiful "Peaches in a White Bowl" from 1910 feels totally different from the industrial landscapes that made him famous, but its off-balance structure foreshadows those compositions. And it's a wonder to see Arthur Dove, who made the first abstract painting in America and maybe the world, channeling Cézanne through Matisse in his lively, highly decorative "Still Life Against Flowered Wallpaper" (1909). It's a style he soon left behind.

And how does Cézanne emerge? The better for it, too. It was these Americans, Ms. Stavitsky has written, who introduced Americans and many American collectors to Cézanne. By paying him so much homage in their works, explicitly acknowledging their discipleship, they helped establish his reputation here as, in the words of both Picasso and Matisse, "the father of us all."