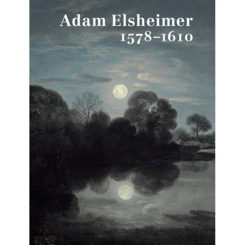

When the National Galleries of Scotland mounted an exhibition of Adam Elsheimer's paintings in 2006, curators subtitled the show "Devil in the Detail" and provided a free magnifying glass in the £6 ticket price. For the cover of the accompanying catalog, they chose an inky, moonlit scene, a detail from "The Flight Into Egypt," which Elsheimer painted in 1609, the year before he died.

It was a perfect choice: the work, owned by Munich's Alte Pinakothek, epitomizes the virtues that made Elsheimer an important figure in art history, even though he produced just 30 to 40 works. Among his disciples were Rubens, Rembrandt, Poussin and Claude Lorrain. When Elsheimer died, Rubens wrote: "Surely, after such a loss our entire profession ought to clothe itself in mourning....He had no equal in small figures, in landscapes, and in many other subjects." The "other subjects" Rubens should have cited are his friend's imaginative handling of narratives, his accurate portrayal of nature, his use of light and, especially, his rendering of night scenes.

In "The Flight Into Egypt," Elsheimer summoned all of those strengths to produce a highly original variation on a then-common theme. Oddly, he was the first artist to portray the scene at night, as it was recounted by St. Matthew, who wrote the only biblical account of the episode.

In "The Flight Into Egypt," Elsheimer summoned all of those strengths to produce a highly original variation on a then-common theme. Oddly, he was the first artist to portray the scene at night, as it was recounted by St. Matthew, who wrote the only biblical account of the episode.

Like almost all of Elsheimer's paintings, this story-within-a-landscape is small, just 12¼ inches by 16¼ inches, and painted on copper, whose smooth, nonporous surface intensifies the luminosity of the oil paint, makes his colors sparkle, and sharpens his minute details.

In the center foreground, set against the dark forest, is the Holy Family. They are fleeing to escape King Herod's diktat that all baby boys in his domain be killed lest one of them replace him. The light from Joseph's torch shines just enough to see bare outlines of Mary, holding Jesus, sitting upon an ass that also bears a few of their possessions. Joseph walks beside them, only slightly more defined by his lamp. Clad in a red cloak, he reaches out affectionately, tenderly, to Jesus.

Off in the distance on the left, much smaller in size, is a group illuminated by a brighter campfire—the painting's second of three light sources. They are shepherds settling in for the night, with their sheep and cows in the shadows nearby. Trying to stay warm, they have not yet noticed the Holy Family. Elsheimer is referencing the shepherds in the nativity story, who received the news of Jesus's birth from an angel and went to him, bearing witness as representatives of all humanity.

Both scenes reside in the lower third of the painting, for what Elsheimer painted here was truly a landscape, as poetic as it is naturalistic. The dark blue sky is vast, dominating the picture. The glowing full moon, reflected in the still lake below, is not a symbol, a white disk, but rather the cratered orb it actually is. It provides the painting's brightest light, illuminating nearby trees and the tops of those farther away. Art historians believe this to be the first realistic moonlit scene in European painting.

It's a starry night, too. A river of tiny, pinpoint stars streams from the top left to the painting's center, disappearing behind the trees just above the Holy Family. The effect is magical, and yet it is the first depiction of the true-to-life Milky Way. Ursa Major is also present, on the far left.

Elsheimer's intricate painting inspires awe in the universe and creates a sense of serenity that belies the anxiety of flight. Both are intentional, art historians have written: They signify the presence of God the Creator, ensuring the Holy Family's escape.

Elsheimer painted "The Flight Into Egypt" while living in Rome. Born in 1578 in Frankfurt, the son of a tailor, he began his art studies there, then moved to Munich. By 1598, he had departed for Italy—first to Venice and in 1600 to Rome. There, he joined the Academy of St. Luke, a distinguished group of artists, associating especially with a circle of Northern Europeans that included Rubens. While in Rome, he converted to Catholicism from Lutheranism; he married and had a son.

Elsheimer painted "The Flight Into Egypt" while living in Rome. Born in 1578 in Frankfurt, the son of a tailor, he began his art studies there, then moved to Munich. By 1598, he had departed for Italy—first to Venice and in 1600 to Rome. There, he joined the Academy of St. Luke, a distinguished group of artists, associating especially with a circle of Northern Europeans that included Rubens. While in Rome, he converted to Catholicism from Lutheranism; he married and had a son.

In Rome, Elsheimer was in contact with astronomers, who by mid-1609 were using telescopes (invented the previous year in the Netherlands) to explore the heavens. Whether Elsheimer used his astronomical knowledge here, or not, was settled in 2005, when the Alte Pinakothek and the Deutsches Museum combined to prove conclusively that he must have had access to a telescope. His celestial landscape accurately represents the position of the moon and stars in the night sky over Rome in June 1609.

Elsheimer is not as well known as he should be; only one American museum, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, owns a painting by him—his daytime version of "The Flight Into Egypt" (c. 1605), an oval measuring 3 inches by 3.88 inches, that was purchased in 1994.

Elsheimer achieved an international reputation in his lifetime, and his paintings were much sought-after. But he was never successful financially, largely because his output was small. Slow and methodical, he would study his subjects assiduously and work from memory. Rubens thought he was lazy, and is said to have chided him. After Elsheimer's death, Rubens criticized his friend for his "sin of sloth, by which he has deprived the world of the most beautiful things." Some experts, though, have posited that Elsheimer suffered from depression.

At age 32, he died in poverty. "The Flight Into Egypt" was his last painting. It hangs in a side "cabinet" gallery in the Alte Pinakothek, and from afar it fails to make any impression. But up close its brilliance is unmistakable.