For the last quarter century, the Cleveland Botanical Garden went all out for its biennial Flower Show, the largest outdoor garden show in North America. With themed gardens harking back to the Roman empire, or an 18th-century English estate, the event would draw 25,000 to 30,000 visitors.

But in 2009, the Flower Show was postponed and then abandoned when the botanical garden could not find sponsors. This year, the garden has different plans. From Sept. 24 to 26, it is inaugurating the "RIPE! Food & Garden Festival," which celebrates the trend of locally grown food — and is supported in part by the Cleveland Clinic and Heinen's, a supermarket chain.

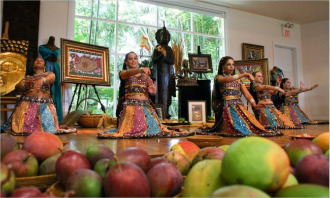

Indian Dancers at the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden in Florida |

So it is across the country. Botanical gardens are experiencing an identity crisis, with chrysanthemum contests, horticultural lectures and garden-club ladies, once their main constituency, going the way of manual lawn mowers. Among the long-term factors diminishing their traditional appeal are fewer women at home and less interest in flower-gardening among younger fickle, multitasking generations.

Forced to rethink and rebrand, gardens are appealing to visitors' interests in nature, sustainability, cooking, health, family and the arts. Some are emphasizing their social role, erecting model green buildings, promoting wellness and staying open at night so people can mingle over cocktails like the Pollinator (green tea liqueur, soda water and Sprite). A few are even inviting in dogs (and their walkers) free or, as in Cleveland, with a canine admission charge ($2).

"We're not just looking for gardeners anymore," says Mary Pat Matheson, the executive director of the Atlanta Botanical Garden. "We're looking for people who go to art museums and zoos."

In May, the Atlanta garden opened an attraction that would fit right in at a jungle park: a "canopy walk" that twists and turns for 600 feet at a height of up to 45 feet, allowing visitors to trek through the treetops. Not far away, food enthusiasts can stop in at a new edible garden, with an outdoor kitchen frequently staffed by guest chefs creating dishes with fresh, healthy ingredients. Edible gardens, along with cooking classes, are the fastest-growing trend at botanical gardens, consistently increasing attendance, experts say.

Visitorship in Atlanta since May is double what it was for the same period last year.

Public gardens across the country receive about 70 million visits a year, according to the American Public Gardens Association. But experts say that because of social trends and changing demographics, attendance is at risk if gardens do not change.

They can, however, take advantage of several trends that could increase garden attendance, including concern for the environment, interest in locally grown food, efforts to reduce childhood obesity, demand for family activities and mania for interactive entertainment. Even economic pressures could help botanical gardens, as more people try to grow their own food. In 2009, 35 percent of American households had some kind of food garden, up from 31 percent in 2008, says Bruce Butterfield, research director of the National Gardening Association. Only 31 percent participated in flower gardening in 2009, about the same proportion as in the last few years.

"There's a generation that will be less interested in gardens," says Daniel J. Stark, executive director of the public gardens association, "but that generation is incredibly interested in what's happening with the planet. Recently, my own two daughters, and a friend, were reading me the riot act about cutting down some trees."

Mr. Stark's daughters are 4 and 8.

Some tactics designed to entice nongardening Americans are not new, of course — exhibitions and concerts have been around for years — but their popularity is growing. The New York Botanical Garden, for example, is drawing big crowds with its current tribute to the poet Emily Dickinson, who was also a gardener.

The new exhibition at the United States Botanic Garden in Washington features "the spectacular spud family," with potato-related artifacts, music and bits of pop culture, with a focus on the endurance of Mr. Potato Head.

Children's gardens are growing more common, as well as more whimsical and interactive, says Sharilyn Ingram, a former president of the Royal Botanical Gardens in Canada who is now a culture professor at Brock University in Ontario. "You get to have a little more fun now," she said.

When the Coastal Maine Botanical Garden, in Boothbay, opened its $1.7 million, two-acre children's garden this month, it came with a chicken coop, where children can harvest eggs; a maze; a bog with carnivorous plants; sculptures of whales, dragons and bears; and a windmill weather station.

In Wyoming, at the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens, the new children's village has adopted sustainability as its theme. It includes a solar-powered discovery laboratory where children can make art from reused materials, a feature that helped it win the highest level of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification.

Teenagers in Cleveland are learning how to grown corn and zucchini on urban plots.

Because of environmental concerns, Descanso Gardens, near Los Angeles, is doing the once-unthinkable: it plans to uproot its historic — but nonnative — collection of camellias, some as tall as 30 feet, which were planted decades ago under the shade of natural woodlands. "It's a fantasy forest," says Brian Sullivan, the director of horticulture and garden operations.

But the fantasy cannot be sustained. Camellias require so much water that it is killing the trees — not to mention being wasteful. Descanso will relocate the camellias, even though some will be lost, and allow the woodlands to return to their native state. "We expect opposition and kudos both," Mr. Sullivan said.

But Descanso still must reach out beyond its aging membership group, he added, so it is remaining open in the evening; offering cocktails (including the Pollinator) at a new Camellia Lounge; breaking ground on a $2.1 million art gallery whose exterior walls will be hung with vertical plant trays that will blend into a turf roof; and maintaining an edible garden dense with fruits, vegetables and herbs that are donated to a local food bank.

Food festivals are becoming a large part of the year-round programming that gardens view as important to winning repeat visitors. In January, the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, Fla., drew some 12,000 people to its fourth International Chocolate Festival with Coffee and Tea. It was followed in April with a local food festival, and this month with a mango festival. In November comes its annual Ramble, a garden party featuring antiques and music.

Fairchild also has an orchid festival.

But showcasing flowers is clearly shrinking in importance. "Most gardens," Ms. Ingram, the Canadian professor, said, "would feel that displaying flowers is necessary, but not sufficient."

This story appeared on Page One of the National Edition and Page A10 of the New York Edition.