State College, Pa.

As America's economic might surged in the last half of the 19th century, culminating in the Gilded Age, a growing class of wealthy industrialists wanted fine art to furnish their grand homes. Elegant portraits, verdant landscapes, and lush still-lifes were popular, and such artists as John Singer Sargent, James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Thomas Eakins obliged.

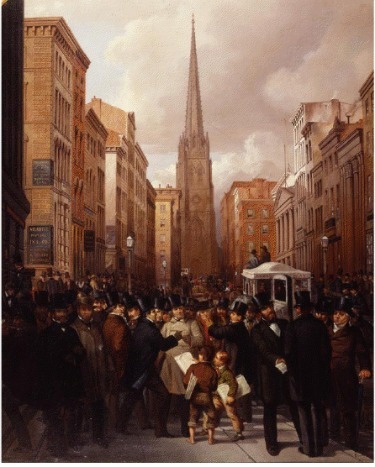

Wall Street, Half Past Two O'Clock, October 13, 1857 |

Fortunately, the exhibition itself is not depressing, for as the catalog notes, artists knew that their paintings could not be too "squalid," or they would not sell. Some, then, put a hopeful gloss on their works, while others injected humor and still others settled for straight reportage.

It is odd, then, that this small exhibition, filling just two of the Palmer's galleries (whose walls have been colored, none too subtly, green), starts out with the saddest, most disturbing painting: "Tattered and Torn" by Alfred Kappes. Mr. Kappes frequently focused on African-American communities, and in "Tattered and Torn" (1886), he portrays an old woman—said to be a domestic servant—in ragged dress, her eyes nearly shut, trying to light what may be her last cigarette with what may well be her last match. Dramatically lit, in bare surroundings that function as a stage, she personifies a depth of poverty that other works in the show avoid. ["Tattered and Torn" is shown on the WSJ site, link above, as is "The Weary Newsboy."]

A better scene-setter, portraying cause and not effect, is just a few feet away, in "Wall Street, Half Past Two O'Clock, October 13, 1857" (1858) by James Henry Cafferty and Charles G. Rosenberg. In this great urban scene, the banking crisis and market crash had begun, and traders, tycoons and people from all over New York City had rushed into the downtown streets. At the center of the narrative, the artists placed two newsboys, whose message ripples through the crowd, changing the looks on faces known and unknown (Cornelius Vanderbilt stands on the far right, for example).

That crisis, and later ones, wreaked their greatest harm on the subjects of many pieces that follow—working men, women and children. The paintings themselves often seem sentimental and benign—with few tatters in sight—until you realize that the sad little girl in John George Brown's "Buy A Posy" (1881) has probably been selling for hours. Her head tilts back, at the same angle as the flowers in her hand, and her eyes implore the viewer to buy one of the many bouquets she has left. Please.

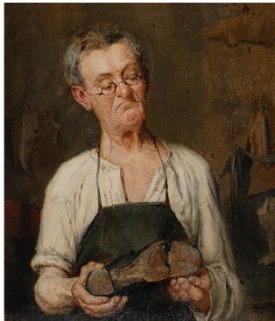

Similarly, Mr. Cafferty's "The Weary Newsboy" (1861), with many more papers to peddle, leans dejectedly against a wooden box, knowing he can't go anywhere until he sells them. And the urchin in David Gilmour Blythe's "A Match Seller" (c. 1859) hungrily devours an apple, a full basket of match boxes at his side. These street children, dependent on their wits and their work for support, deliver a message that's hard to ignore.

A Difficult Job |

For its size—about 30 academically informed, narrative paintings and a few etchings, including one of beggars by Mr. Whistler—this exhibition covers a lot, indeed too much, ground. The have vs. have-not dichotomy surfaces in a few works, like Thomas Waterman Wood's "Crossing the Ferry" (1878) where the upper classes reach into their pockets and purses to give coins to a waif playing a violin; and in "Evading the Excise Law—Laying in Rum for Sunday" (1867), an engraving by Stanley Fox that depicts a Saturday night scene in a New York rum shop (and is the only actual reference to taxes in this preincome-tax era). The male vs. female experience is shown in Charles Knoll's "Panic of 1869" (1869) depicting a ruined businessman hiding his face from the news while his wife, a baby at her feet, holds his hand and looks away. Westward flight is represented by William de la Montaigne Cary's "Pikes Peak's or Bust." And the famed election of 1896, with its debates on monetary policy and the gold standard, is immortalized in Victor Dubreuil's "The Cross of Gold" (1896) five currency notes nailed to a brown wall. And that's just a sampling; the works whirl through a dizzying array of topics.

Perhaps that is because the show itself was the victim of the current recession. Originally, it was conceived as an exhibit of about 70 works, with a catalog—now about 75 pages—longer by 200 pages. Shrunken by the times, it's quirky and uneven, but it does remind viewers of this neglected genre of American art.