HOUSTON — In the music world, it's now axiomatic that opera companies must change, that they can't just keep staging the same old productions of "Tosca" and "Carmen," that they must shed their snooty image if they want to thrive. But how?

Anthony Freud, the London-born general director of the Houston Grand Opera, has staked out an answer all his own. He calls it "HGOco," and says that when he moved here in 2006, coming to "a 21st-century city" with "a 400-year-old art form," it was absolutely essential. "We had to establish a dynamic, groundbreaking relationship with our city and not be nervous about establishing relations with Houston's communities," Mr. Freud said when we met in his office recently.

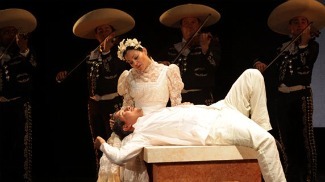

Scene from "To Cross the Face of the Moon" |

So, in 2007, "The Refuge" took the stage. Written by Prix de Rome-winning composer Christopher Theofanidis and librettist Leah Lax, it drew on Ms. Lax's interviews with about 150 African, Central American, Indian, Mexican, Pakistani, Soviet-era Jewish and Vietnamese immigrants to Houston. Mr. Theofanidis integrated instruments and musical material from each culture in his score.

In 2010, "To Cross the Face of the Moon/Cruzar la Cara de la Luna," a mariachi opera composed by José "Pepe" Martínez with a libretto by Leonard Foglia, made its debut in a concert version. The plot reveals the secrets of three generations straddling two cultures—a Mexican-American man with an immigrant father and a daughter born in the U.S.

And in two performances this month, "Courtside," the first of nine chamber operas that will deal with Asian immigrants under the umbrella name "East + West," is having its premiere. Composed by Jack Perla for an ensemble of violin, cello, bass, vibraphone and pipa, with a libretto by playwright Eugenie Chan for a cast of four, its story is about reconciling pride in modern America with Chinese tradition across three generations. It will be performed in community centers around town.

Anthony Freud |

Rather, he says, "These programs are ends in themselves, not means to something else." In the course of our interview, he restated his philosophy about opera companies several ways:

"Every opera is a cultural services company."

"Opera in general, the art form, is strong, but we have to be prepared to think laterally and radically."

"We can't exist in a hermetically sealed bubble. We have to break down barriers and engage people on their own terms, not ours."

"HGOco is a lab and a playground, an initiative to reach a very large number of people who may not normally get involved with an opera company."

Mr. Freud is not one of those people: His roots go deep. He saw his first opera, "Hansel and Gretel," at age 4. Though he was more enamored of the banana ice creams he devoured at intermission (his parents refused his request for a third) than what was happening on stage, that soon changed. With one or the other of his Hungarian immigrant parents, he began attending opera (plus theater and ballet) regularly; then—in his early teens—he started going alone, three or four times a week. By 14, he says, "I wanted to run an opera company."

He studied law, picking King's College, London, because it was "halfway between Covent Garden and the National Theatre." Though called to the bar, he soon defected to his true love. From his first job as assistant to the director at Sadler's Wells Theatre, he jumped to the role of company secretary and planning director at the Welsh National Opera and to an executive-producer post at Philips Classics records before landing his dream job: In 1994, he was named general director of the Welsh National Opera.

In Houston, Mr. Freud succeeded a local hero, David Gockley, who in his 33-year tenure elevated the Houston Grand Opera from sleepy regional house to national stature, with the fillip of being a powerhouse of new opera.

But as Mr. Freud tells the story, the HGO board was ready for more. "It seemed to have an appetite for new ideas, new strategies, new ways of doing things," he says. Hence HGOco, which in the past three years has reached 600,000 people. "We know that they are not our regular customers," he adds.

Yet doesn't this structure bother him? It has the semblance of a two-tier system, with mainstage productions in a grand theater remaining the province of old-guard opera-lovers, while everyone else gets something different, often outside the opera house. "I don't see two levels," Mr. Freud says, "though I see the danger of that perception." He says some HGO patrons do go to the HGOco productions, and some people exposed to HGOco operas have purchased tickets to mainstage works. A donor has underwritten the recording of "The Refuge," and Mr. Freud has raised money to record the mariachi opera. Companies in France and Australia have already shown interest in staging "To Cross the Face of the Moon."

"It's not a matter of either/or," Mr. Freud continues. "It's both. We can do more than mainstage opera."

Warming to the defense, he adds: "HGOco produces opera on their terms, not on our terms. Call it opera, don't call it opera—I don't care. But only something like a classic HGO could do something like 'The Refuge.'"

In fact, back at the mainstage, Mr. Freud is equally adamant about change. He is continuing HGO's support for new works and planning a new "Ring" cycle with Opera Australia, among other things. No one, he says, would suggest that movies should continue to be made as they were in the 1950s. "The way we produce opera ultimately has to change," he says.

But, while proud of what he has done, Mr. Freud is not suggesting that he has invented opera's future. "I don't believe in a generic approach to a generic opera company," he says, "but what we're doing here should have relevance in every U.S. city."