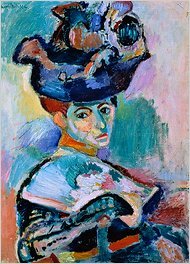

THE exhibition that opens at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art on May 21 is certain to be a dazzler: "The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso and the Parisian Avant-Garde" will have 40 works by Picasso, 60 by Matisse and many by favorites like Bonnard and Cezanne. Picasso's "Gertrude Stein" will be there, with his "Boy Leading a Horse." So will Matisse's wildly colorful "Woman With a Hat," which was derided by critics when revealed in 1905 but was soon purchased by the Steins for what would become their pioneering collection of modern art.

Matisse's Woman With a Hat at SFMoMA |

Museum officials are likely to appreciate the show for all that and an additional reason. To many, "The Steins Collect" will be persuasive evidence that organizing an exhibition around the collector's eye is a legitimate and valuable practice.

Every now and then, a furor erupts over just such exhibitions, which, when the collectors are alive, are rife with potential conflicts of interest. It happened in 2009, when the New Museum in New York exhibited works from the collection of Dakis Joannou, a trustee, and in 2010, when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art displayed 100 works owned by the trustee Lynda Resnick and her husband, Stewart. And it happened in 1999, when the Brooklyn Museum displayed works owned by the British advertising magnate Charles Saatchi.

The circumstances always vary, but what single-collector exhibitions share are aspects that challenge their legitimacy. When the collectors are trustees or provide financing for an exhibition, it looks as if the museum is selling out to vanity shows or renting its galleries. If museums show a collection without the promise of a gift, they are seen as endorsing the art and elevating its value. If museums display art that comes with a gift, they seem — unless it is the entire collection — to be using a questionable fund-raising tool at best, or exacting a quid pro quo at worst. The question always arises as to who is making the curatorial decisions, museum or collector? And when collectors sell art after the exhibition, the museum looks as if it has been used.

But rather than avoid these shows, museums around the country are embracing them. Last summer, the Metropolitan Museum of Art displayed Italian drawings from the collection of the honorary trustee David M. Tobey and his wife, Julie; this spring, the Katonah Museum of Art in Westchester County is showing works on paper from the Sally and Wynn Kramarsky Collection; and on Saturday, the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh will open "30 Americans," highlighting works by African-Americans in the Rubell Family Collection in Miami.

Works Owned by Judith Neisser on view at the Art Institute of Chicago |

Meanwhile, exhibitions including "Beauty and Power: Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes from the Peter Marino Collection" and "Golden: Dutch and Flemish Masterworks from the Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Collection," are traveling the country.

Why are they all risking criticism? Borrowing a collection from a patron is an easy way to show material a museum does not have. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, for example, aspires to be an encyclopedic museum but owns almost no Native American art; to fill that gap, it is displaying pieces from the collection of two longtime donors, Robert and Nancy Nooter. "Museums exist to educate the public and delight them; it makes sense to feature these collections if you can," said John Ravenal, curator of contemporary and modern art at the Virginia museum.

Searching to provide the public with new reasons to come, museums in these tight times are also turning to single-collector exhibits for economic reasons. Compared with exhibitions drawn from many sources, they are "always cheaper," says James Cuno, director of the Art Institute of Chicago. Budget items like shipping costs are lower.

Yet museums prefer to emphasize the value of looking at art through the eye of a collector. Because collectors are free to indulge their vision, venturing into new or unfashionable areas, they can lead taste. They can also collect an artist or a period in depth. The van Otterloo collection is an example: its 70 Dutch and Flemish paintings were purchased over the last few decades by the couple to illustrate every genre by master painters of Holland's 17th-century Golden Age. It is worth $250 million or more, and no museum today could afford to assemble it.

Purchases by museums tend to be more conventional, reflecting taste and covering the bases, rather than specializing. That is due, in part, to a lack of money. Also, Mr. Ravenal explains, "for museums to acquire, it's a laborious, multistage process, and sometimes a dealer won't hold on to a work through it." Typically, museum purchases must pass muster with trustees.

Not every collector has had as much foresight as the Steins or as much focus as the van Otterloos, of course. But Mr. Cuno notes similar "moments" of collector boldness in Chicago. "There was one around Monet, who was alive when our collectors collected him, and the richness of our Impressionist collection is a result," he says. "And there was one around surrealism," when the Art Institute patrons Lindy and Edwin Bergman in particular bought works by Dali, Tanguy and others, which were given to the museum.

Chicago has been having another moment, Mr. Cuno says, and with his current series of single-collector exhibitions, he is simply "documenting the taste of Chicago collectors" in recent years. He wanted to do so now because in 2009 the Art Institute opened a wing for modern and contemporary art that he said had created "tremendous pride" and prompted many gifts of art. Of the 100 works in the Neisser show — by minimalist and conceptual artists of the 1960s, and later artists with similar themes — 33 are promised gifts. The Stones are donating 50 works that were in last fall's exhibition.

In presenting "Conversations With Wood: Selections From the Waterbury Collection" this summer, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts has many motives. Jennifer Komar Olivarez, an associate curator, is choosing what to display from the collection owned by David and Ruth Waterbury, longtime museum patrons. "This is an exhibition to honor and engage with this couple because they have been so supportive to us," she says. "I want to show the best of the collection; whether they come to us is a separate issue." Still, she knows that "they are thinking about the dispersal of the collection" and that other museums are interested in it.

At the same time, Ms. Olivarez said that showcasing the Waterbury collection provided a different opportunity.

"Wood is an area where you can buy without much money and get involved with the artists," she said. "This exhibit will get people to think about outside-the-box collecting areas, and museums are interested in fostering collecting."

As expected, curators play down collectors' challenges to their curatorial decisions. "You have to navigate the wishes and whims of the collector, but they can be managed," says Mr. Ravenal, who is president of the Association of Art Museum Curators. Ms. Olivarez said, "It's an educational process on both sides and finding mutual respect." Curators also point out that today many collectors, as museum patrons and trustees, buy art with donations in mind, consulting with curators as they buy.

Fair enough, says Nicholas Fox Weber, the author of several books on collectors, but he raises a pertinent point, made more so by art market trends. "One great problem today is that we have rich people who buy indiscriminately," he says. "They are not showing a vision." Mr. Weber tells of a recent forum of collectors where, he says, "they could have been saying 'we have one Prada, one Louis Vuitton, one Gucci.' It troubles me when they have one Warhol, one Jasper John and so on. What's interesting is if you have an original collection."

Mr. Weber says he does not want to restrict single-collector exhibitions, but he urges museums to be more discriminating about them. "It's up to the museum director only to show a collection if there is a vision," he says.