If they've got money to squander like this—of a crucifix being eaten by ants, of Ellen DeGeneres grabbing her breasts, men in chains, naked brothers kissing—then I think we should look at their budget. [It's] in-your-face perversion paid for by tax dollars.

— Rep. Jack Kingston (R–GA) on FoxNews

A strong show, the first queer-themed exhibit in a national museum, it nevertheless would have been as conspicuous as rain on a distant sea if it weren't for a few dank straight men who hate gay people.—JoAnn Wypijewski in The Nation

Jed Perl's . . . dithering "art for art's sake" formalism engages nothing but its own reactionary yearnings; one wonders if he wears rubber gloves when he types, the better to prissily avoid the messiness of lived history.

—David C. Ward and Jonathan D. Katz, in a letter to The New Republic rebutting Perl's commentary on the exhibit

Hmmm. Shall we file the recent debacle at the National Portrait Gallery under "Return of the Culture Wars," "Homophobia," "Christian Bashing," "Media Circus," "Politics As Usual," or "Men Behaving Badly"? All of the above would be accurate. But "Men—and Women— Behaving Badly" seems most appropriate. Nearly every person or group who claimed a part in this sorry episode in American cultural history exacerbated what should have been a minor incident, or perhaps not an incident at all.

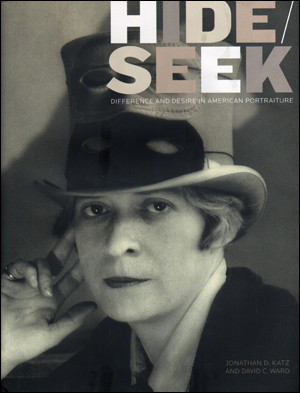

To recap, briefly: The gay-themed exhibition at the center of this fury, "Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture," on view at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington from October 30, 2010 through February 13, 2011, was hardly X-rated, but it did include several artworks that, in the hands of social conservatives, might be used to stir up trouble. David Wojnarowicz's four-minute pastiche film "A Fire in My Belly," which showed a statue of a crucified Christ covered with honey and ants, proved to be most exploitable: It hit two hot-buttons, homosexuality and religion. So when people like Representative Kingston, a member of the appropriations committee, attacked, the Smithsonian Institution, which includes the NPG, feared for its money and caved. Within hours, the NPG removed the film, causing a reaction among liberals that more than equaled the initial assault. They coupled over-the-top rhetoric with repeated showings of the "offending" video in museums and galleries around the country; the reverberations continue today.

To recap, briefly: The gay-themed exhibition at the center of this fury, "Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture," on view at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington from October 30, 2010 through February 13, 2011, was hardly X-rated, but it did include several artworks that, in the hands of social conservatives, might be used to stir up trouble. David Wojnarowicz's four-minute pastiche film "A Fire in My Belly," which showed a statue of a crucified Christ covered with honey and ants, proved to be most exploitable: It hit two hot-buttons, homosexuality and religion. So when people like Representative Kingston, a member of the appropriations committee, attacked, the Smithsonian Institution, which includes the NPG, feared for its money and caved. Within hours, the NPG removed the film, causing a reaction among liberals that more than equaled the initial assault. They coupled over-the-top rhetoric with repeated showings of the "offending" video in museums and galleries around the country; the reverberations continue today.

It is reasonable to ask whether the eleven-second passage in Wojnarowicz's film merited the inflamed criticism it drew from the right to begin with. It also is reasonable to ask what would have happened had the Smithsonian suffered the complaints, which were narrowly based, and defended curatorial authority. And it is reasonable to ask whether the art world over-reacted, stoking the fire with heavy-handed cries of censorship and stick-in-the-eye acts of provocation. But measured actions were not to be, and once they were not, the molehill became a mountain. No one much tried to calm the hysteria for the simple reason that so many people saw ways to use this manufactured controversy to their advantage. There was some principle involved, yes, but even more shameful exploitation. Many parties made the mountain bigger for their own gain, be that politics, notoriety, publicity, or money.

"Hide/Seek" turned out to be quite aptly named. The aftermath begs us to seek out what actually happened and who is hiding behind what. Here was the premise of the show: In the days when homosexuality was a matter to be concealed, artists embedded clues about their sexual proclivities into their work, like a code. The signs were there for all to see if only viewers looked, and the exhibit provided ample illustration. Once these examples were out of the closet, the hidden impact of gay and lesbian artists would be clear. "Hide/Seek reconsiders neglected dimensions of American art," wrote Martin E. Sullivan, the NPG's director, in his foreword to the catalogue. "It has necessitated asking new questions and risking new interpretations, some of which may challenge accepted canons of art history."

Both statements are something of an exaggeration. The sex lives of many artists in the show—Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Romaine Brooks, and Robert Rauschenberg, to name a few—have long been known and explored. When The New York Times critic Holland Cotter wrote his review of the show, published on December 10, he admitted that when he had first looked at the catalogue—before the controversy—he had "felt a bit let down" by its contents. He called it a "pride" display of little interest. (He later reconsidered.)

The exhibition's co-curator and Perl-antagonist, Jonathan Katz, who is the director of the visual studies doctoral program at the State University of New York-Buffalo and a longtime proponent of queer studies, ends his essay for the "Hide/Seek" catalogue with a kind of requiem for the era. After explaining how "historically queer art has drawn power from oppression and from the inventiveness, ingenuity, and originality it encouraged as a strategy of survival," Katz writes that that era may be over, given the openness of homosexuality nowadays. "Absent constraints, after all, queer portraiture would not need to look or operate any differently than any other portraiture. In time, perhaps this book itself might be viewed as something akin to a survey expedition, a means of chronicling a species just prior to its disappearance."

It was a sunny but chilly Saturday in Washington last October 30 when "Hide/Seek" opened. It received no preview in the Washington Post, and it did not create a stir. On the following Friday, the Post did print a review. The art critic Blake Gopnik liked the exhibit, saying it portrayed a "fascinating world" and contained "powerful art." He called it "one of the best thematic exhibitions in years." Among the works he singled out were those by the photographer Carl Van Vechten and the painters Thomas Eakins and Andrew Wyeth, the last of whom, "though apparently as straight as they come," painted a "gay cheesecake" frontal nude of his young neighbor. Gopnik did not mention Wojnarowicz's "A Fire in My Belly."

There things stood for about a month. The National Portrait Gallery is not located on the Mall, to which so many tourists flock—it's four longish blocks away, in the old U.S. Patent Office. Visitors have to go there on purpose, and NPG's exhibitions, which in recent months have included a show of presidential portraits from the cover of Time magazine and a juried portrait competition, do not usually draw blockbuster crowds. Throughout November, museumgoers came and went; neither the exhibition nor Wojnarowicz's video attracted notoriety.

Someone on the right must have noticed it, however, and tipped off the Christian News Service, an organization founded by L. Brent Bozell III to counter "liberal bias in many news outlets." On November 29, an article by Penny Starr appeared on CNS, calling attention to a Smithsonian "exhibition that features images of an ant-covered Jesus, male genitals, naked brothers kissing, men in chains, Ellen DeGeneres grabbing her breasts, and a painting the Smithsonian itself describes in the show's catalog as 'homoerotic.'" It's hard not to notice the similarity to words later used on FoxNews by Representative Kingston.

Starr highlighted the most "sensational" works, which are a small part of the exhibit, and mostly quoted from the catalogue and the exhibition labels to describe them. The article makes a hokey connection, in both the headline and the text, to the Christmas season, as if the timing of the exhibition were a calculated affront to Christians—a theme also repeated later by House members. She also noted that the NPG had hosted a family day built around "Hide/Seek," with hands-on art activities for children, and questioned Katz's co-curator Ward whether "the exhibit might be offensive to people who disagree with the homosexual lifestyle." He responded by calling the American public tolerant and mature.

The next day, CNS was back with a story titled "Boehner and Cantor to Smithsonian: Pull Exhibit Featuring Ant-Covered Jesus or Else." By "or else," House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) supposedly meant that the Smithsonian will "face tough scrutiny when the new Republican majority takes control of the House in January." And, Starr wrote, "House Majority Leader-to-be Eric Cantor (R-VA), meanwhile, is calling on the Smithsonian to pull the exhibit and warning the federally funded institution that it will face serious questions when Congress considers the next budget." Cantor called the show "an outrageous use of taxpayer money."

A disclosure before moving on: I did not see the exhibition, but I do have the catalogue, and I see little in it that is more explicitly sexual than, say, Egon Schiele's drawings of female nudes or the reams of classical images of Cupid and Psyche or Susannah and the Elders. Occasionally, the tone is different: a few of the pieces seem more like "provocations" than "art" (they could be both, of course), but such judgments are a matter of taste, not fact, and thus debatable. The Wojnarowicz film is not in the catalogue (none of the videos are).

Right and left, news organizations from FoxNews to The Los Angeles Times jumped on the story. So did blogs. (In early April, a Google search of "hide seek art exhibit" produced more than 3.1 million results.) Soon after CNS's November 30 article, "A Fire in My Belly" was removed from the exhibit, and the real firestorm began. On December 1, the Post published "Ant-covered Jesus video removed from Smithsonian after Catholic League complains."

Martin E. Sullivan, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, attached his name to the removal statement, which acknowledged that Wojnarowicz's images "may be offensive to some" but said they were not "intentionally sacrilegious." But most reports of the removal used the passive voice; the Post reported that "the decision to remove the video was made after Sullivan consulted with Richard Kurin, a Smithsonian undersecretary, and representatives of the offices of government affairs and communications."

The Smithsonian Secretary G. Wayne Clough, an engineer by training who took the Smithsonian job in mid-2008 after serving as president at the Georgia Institute of Technology—but with no experience in the art world—made the call. He had consulted with Kurin, a cultural anthropologist and folklorist, who became the acting Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture in late 2007, after the departure of the former Undersecretary for Art, Ned Rifkin. Rifkin had been a museum director before, and is again, and his position had been created in 2004 to raise the profile of and coordination among the Smithsonian's art museums. But Clough folded his job back into one position, promoting Kurin, who also had no curatorial experience. That lack hurt—Clough later said he regretted acting hastily—probably leading him to underestimate the intensity of the reaction: uniform condemnation from artists, foundations, museums, galleries, and those who saw homophobia, not religious objections or something else, as the reason for the withdrawal. And, maybe, for some censurers, it was. CNS had tried to play up the gay angle (asking about family day and citing the DeGeneres photo, which exposes nothing more scandalous than her midriff). But those points never resonated.

And once the Wojnarowicz piece was removed, the right, by and large, stepped back from the commotion, and the left took over. Criticism of the NPG was construed as an attack on free expression of artists and the mood was all-for-one-and-one-for-all. The Washington Post called for Clough's resignation. On December 3, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD)—a group of nearly 200 museum chiefs not normally given to quick action—released a statement saying, in part:

More disturbing than the Smithsonian's decision to remove this work of art is the cause: unwarranted and uninformed censorship from politicians and other public figures, many of whom, by their own admission, have neither seen this exhibition as a whole or [sic] this specific work. . . . The AAMD believes that freedom of expression is essential to the health and welfare of our communities and our nation.

Essential, but not, apparently, allowed for those who disagree with AAMD. The cries of "censorship" aimed at Cantor, Boehner, and others should have been directed solely at Smithsonian officials, for it was only they who had the power to censor. Boehner and Cantor could not have removed the piece or, on their own, cut the Smithsonian's budget, and they are entitled to voice their opinions.

Museums, individually, joined the protest, too. The New Museum in New York immediately put the film on view, as did the Smith College Museum of Art, the Walker Institute of Art, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, and many more. The Museum of Modern Art went one better: in addition to showing the video, it announced that it would acquire "A Fire in My Belly" for its permanent collection. Commercial galleries, aided and abetted by Wojnarowicz's New York gallery, PPOW, which made copies of his video available to pretty much any public space that wanted to show it, jumped on the opportunity. One put it on display in its window. College gay groups sponsored screenings as well.

One group called art Positive, formed to organize "direct action against the censorship," even drew supporters into the streets of Washington and New York in protest. Well-known art critics joined in, no longer satisfied with using words as weapons. According to Art in America magazine, Jerry Saltz, of New York magazine, and Roberta Smith, of The New York Times, joined Lisa Phillips, the director of the New Museum, the former Metropolitan Museum of Art general counsel Ashton Hawkins, and perhaps 500 artists, curators, activists, and gay and lesbian supporters one Sunday afternoon. The crowd marched from the Met to the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, also part of the Smithsonian, carrying signs that read "Smithsonian stop the censorship," "Free speech bitch," "Stop homophobia," and "Silence = Death."

Saltz also blasted the aforementioned Perl, who had dismissed the controversy as "people acting like mob-selves" in The New Republic. Answering a question about Perl on his blog, Saltz called him "cynical, stingy, and churlish," as well as "ultra conservative," and wrote: "Fools rush in: One prominent and depressing aspect of the culture wars has been how fast they make people stupid." Some of this reaction, as Saltz put it, was "solidarity." But it hasn't hurt the profile of, say, the Canadian artist A. A. Bronson, who swiftly demanded that the NPG remove his work, a photograph showing the body of his partner shortly after he died of AIDS, which is also in "Hide/Seek." That gesture is now part of his Wikipedia entry. (Despite backing for Bronson, the NPG refused.) Neither has it hurt the career of Jonathan Katz. Rightly, The New York Times recently labeled him as "something of a gadfly," and he's now got lecture dates on the whole fiasco.

In a free country, some of this is healthy. What is surprising, and disheartening, is the pumped-up hysteria and the vitriolic language used by both sides. Words and phrases like "vile," "American Taliban," "hate speech," "conservative noise machine," "in your face perversion," "tyranny," and "religious crusade" have pervaded the rhetoric. It is no longer safe to raise a measured voice—or to disagree; attacks immediately ensue.

Make no mistake: I think Clough erred in pulling the film. It is wrong for the Smithsonian secretary to vet exhibitions after they are mounted, after any particular constituency—right, left, or center—objects. The time for vetting and weighing sensitivities is before an exhibition begins. All of the works chosen by Katz and Ward for "Hide/Seek" should have been reviewed and approved by the museum's director. If any were thought to be problematic, or if Sullivan thought the exhibition or any work in it would cause a commotion that reflected on the Smithsonian as a whole, he should have alerted Kurin or Clough or both—that was the point at which to weigh in. Once an exhibit is on display, it should stand, or the person whose authority was usurped should resign (or be forever crippled). Museums should not be subject to what one protester called the "heckler's veto."

Nor should the left allow the right to determine the worth of an artist. For no doubt about it, this episode has turned into a great career move for Wojnarowicz, who died in 1992. PPOW recently gave him an exhibition titled "Spirituality," displaying works from 1979–90 (it ran March 3 through April 9): "Controversy has introduced David Wojnarowicz—artist, writer, AIDS activist, and legendary figure of the 1980s downtown scene—to a new generation nearly twenty years after his death," reads ArtForum's online review of the exhibit. There are hundreds of gallery exhibitions in New York at any one time; astonishingly, The Washington Post reviewed the show. There have been all those video showings and acquisitions. There's even a website, called www.hideseek.org, to keep track of all the activities related to "Hide/Seek," and a Twitter feed for updates.

There's a simple, well-worn remedy for exhibitions or legitimate pieces of art that may offend or be too explicit for the general population: warn people and let them choose to enter or not. On December 6, the NPG announced that it had done just that: the museum said it had installed signs reading "This exhibition contains mature themes" at both entrances of the show.

Might it all have ended there? Not any more, not in today's political climate. Museum directors, curators, and other denizens of the art world will tell you that it would be wrong to let the right's "victory" stand, that this would only encourage more aggressive acts against contemporary art and/or gay rights. But in the near term, at least, the controversy worked to the NPG's favor and also to the advantage of all those other banner brandishers. What would have been a nice but barely noticed exhibit turned into a cause célèbre. The Times, for one, may never have reviewed it, but Cotter went on to pronounce that the curators "have assembled a historical show with a very specific slant, but with rewards for everyone." Around the country, the show was suddenly labeled "groundbreaking" (ARTNews) and "critically acclaimed" (The Los Angeles Times). Attendance at the NPG climbed.

Worse, when this theater of the absurd collided with reality, no one paid attention to the actual artwork in question. From the start, the National Portrait Gallery portrayed "A Fire in My Belly" as a comment on AIDS. The Washington Post, for example, quoted Sullivan saying, "The artist was very angry about AIDS and he was using that style to create a statement about suffering. His approach was based on a lot of imagery that is very Latin American, and it can be garish and unsettling." Everyone, not surprisingly, repeated the interpretation.

Except it wasn't accurate. As the Wall Street Journal pointed out on January 31, Wojnarowicz's executor and one-time partner, Tom Rauffenbart, said the artist didn't have AIDS or anything to do with the AIDS movement at the time he made the film. According to Rauffenbart, the WSJ said, "it is questionable if it was created as a response to AIDS" at all. If there has been a single correction, I haven't seen it, and only a few publications have written anything about this part of the story. Why does the misinformation continue?

Neither side in this mess wants to engage with the other; they have their own purposes in mind. But if disputes like this are not framed properly, let alone debated well, they will never be resolved. We will return to the cultural wars, because both sides behaved badly. They may claim that they won—and both did win something. But the arts lost.