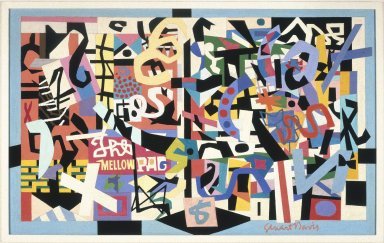

Welcome to "The Mellow Pad." Can you sense the jazz that inspired it? Are you feeling the rhythm, getting into the mood?

Stuart Davis would be pleased. A cheerful medley of shapes in bright pinks, blues, yellows, greens, black and white, "The Mellow Pad" is his evocation of, and homage to, the hip life spawned by the Jazz Age. He wanted this kaleidoscopic picture, which hangs in the Brooklyn Museum, to convey a feeling, rather than depict an actual, physical place.

The Mellow Pad, Courtesy of The Brooklyn Museum/Stuart Davis Estate |

Equally important, Mr. Davis was intent on becoming a distinctly American modernist. He adapted Cubism's flattened perspective and Fauvism's bold, saturated colors to create a unique style. At the same time, steeped in the Ashcan school's ethic of portraying the truth of urban life, Mr. Davis expanded the definition of what constituted "life" to include consumer culture—eggbeaters, matchbooks, cigarette packs and bottles of mouthwash. To him, his paintings were not "abstract"—because they all derived from something he had seen or experienced. In this fusion of the forms of European modernism with native subjects, he created an art that was thoroughly new and American.

In his teens, Mr. Davis had started visiting bars in Newark, N.J., and Manhattan to hear jazz, and he became a lifelong fan, often hanging out with jazz musicians. He once said that jazz was one of the things that made him want to paint, admittedly along with gasoline stations, synthetic chemistry, 5 & 10 cent store kitchen utensils, fast travel, electric signs, movies and radio, Gloucester, Mass., and a half-dozen other things. But he also credited jazz specifically with influencing the development of his vibrant style.

The title "The Mellow Pad" has an obvious reference—"pad" being hipster slang for an apartment or home—but it denotes both more and less than that. Mr. Davis played down the significance of "pad" in his titles, saying it was just a word that amused him. But in jazz-talk, a "mellow pad" refers to an emotional state, a sweet spot experienced while giving a sizzling performance, say, or listening to one—and that's the feeling Mr. Davis was striving for.

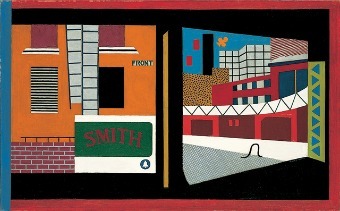

Mr. Davis began painting "The Mellow Pad" in 1945, but its origins lie in an earlier work, "House and Street" (1931), now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. The left half of "House and Street" shows the facade of a building in downtown Manhattan painted in brilliant orange and red, and bisected vertically by two fire escapes. On the right half, he juxtaposed a brightly hued street scene, with a factory chimney and skyscrapers. The two halves are separated from each other by a central divide and framed by a primarily black surround. In this painting, Mr. Davis reduced all the forms to flat, intensely colored geometric shapes. And as he often did, he incorporated words—"Front," which refers either to the name of the street or the side of the building we're looking at, and "Smith," which may allude to 1928 presidential candidate Al Smith. Strikingly, he angled the perspective of the "Street" side of the painting, effectively putting the viewer in two places at once.

House and Street, Courtesy of The Whitney Museum/Stuart Davis Estate |

He showed the first version of "The Mellow Pad" two or three times in 1945. By 1947, he was back at work on it, making numerous sketches and trying out new ideas in four smaller riffs on "House and Street." One of these, "Pad No. 4," also in the Brooklyn Museum, shows Mr. Davis developing the vocabulary of shapes he used in "Mellow Pad," according to Teresa Carbone, the museum's curator of American art. But, she adds, it is not a preparatory sketch for it.

Mr. Davis believed in "well-built" pictures and, while it's not obvious, "The Mellow Pad" has a structure. Like "House and Street," it is bifurcated by a central divide and framed by a painted surround. It also repeats several iconographic elements from "House," among them the brick building front on the lower left (now in green and yellow, instead of red), the orange house facade and the right-hand side's black smokestack.

From there, Mr. Davis took off, filling the canvas with a mixture of dots, arcs, curves, crosses, squiggles and other shapes, only a few of which have any relation to real objects. Always a brilliant colorist, he chose a cool palette for his mellow pad, but also an unruly one—an abundance of intense shades. Between the colors and the shapes, the picture almost vibrates. Indeed, Mr. Davis here manages to create a pictorial equivalent of syncopation through the irregular visual rhythms created by his loosely ordered arrangement of forms and colors.

Mr. Davis reveled in the results. In an entry on his calendar dated March 3, 1951, he wrote that in redoing the upper left-hand corner, which he called "Hell's Corners," he had experienced "probably the most powerful objective Art realization of my life." He felt he had achieved his goal of painting a picture that conveys the experiencing of being in a jazzy space, without portraying it representationally.

Witty and high-spirited, "The Mellow Pad" invites viewers to linger in another world, to feel the painting's pulse, and enjoy it.