Recently the director of a major American museum was gently venting about collecting contemporary art. Curators in that field, he said, are too attuned to the market, too eager to collect works by artists early in their careers, lest they be shut out later if prices rise beyond museums' means. As a result, museums are acquiring many works that will not stand the test of time.

Demuth's "My Egypt" |

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the museum's founder, also vacuumed up a lot of contemporary art. But instead of rushing to judgment in the face of too much demand, Whitney was buying when most collectors in the U.S. favored European art. An artist herself, she thought that living American artists were underappreciated, and bought works to support them. By 1929, she owned more than 500 objects, and when that year her offer to donate them to the Metropolitan Museum of Art was declined, she decided to start her own museum and intensified her purchases. With Juliana Force, the museum's first director, she bought an additional 200 works before the Whitney opened in 1931, and another 200 in its first years. When deeded to the Whitney in 1935, this founding collection consisted of about 1,000 works of art.

For the current exhibition, about 100 paintings and sculptures have been selected by co-curators Barbara Haskell and Sasha Nicholas—but not because they are the best. As the Whitney plans its move from Manhattan's Upper East Side to new, larger quarters downtown, curators are reviewing its 18,000-object collection with fresh eyes, organizing six chronological exhibitions and experimenting with new display approaches that might be used in the new galleries. "Breaking Ground," the first, consists mainly of works by lesser-known artists that have a contemporary resonance but haven't been shown in decades. Mixed with a few renowned works, like Edward Hopper's "Early Sunday Morning" and Charles Demuth's "My Egypt," the sampling is meant to be representative of works of the era.

And what a period it was. During these years—roughly 1902 to 1935—artists in Europe were creating several strains of modernism. Leading-edge artists here joined in after the 1913 Armory Show, where they saw works by the likes of Paul Cézanne, Marcel Duchamp and Henri Matisse. Others, however, knew little of or ignored the innovators, and in buying art Whitney not only favored these representational artists but also bought with an inclusive, all-embracing approach.

The exhibition fills six galleries, arranged loosely by theme rather than chronology. The first mimics the entrance to the museum's precursor, Whitney's Eighth Street Studio Club: Its rounded walls enclose a few sculptures, and contain niches filled with Richmond Barthé's graceful "African Dancer" on the left and Whitney's own "Chinoise," a serene self-portrait, Asian-style, on the right. They serve their purpose, which is not to dazzle with artistic brilliance but to take visitors back in time.

The next gallery is filled with landscapes, but within view is a room hung "salon-style"—from floor to ceiling, in other words—with 43 paintings, and fitted with two plush sofas, and that is the best place to begin. (Whitney, after all, sought to make her museum informal and intimate, and she wanted visitors to meander as they pleased.) Grouped near the salon gallery's door are the first four paintings Whitney ever purchased: Everett Shinn's dramatic theater scene "Revue," Robert Henri's sweet "Laughing Child," George Luks's homey "Woman With Goose" and Ernest Lawson's placid "Winter on the River."

All four men were members of "The Eight," who painted scenes of urban life in the unidealized, brushy style that became known as the Ashcan School, which Whitney championed. In fact, everything in this room is by artists she supported with stipends, travel grants or regular purchases. None of the works, though, would rank among the artists' best. The Luks is muddy; the Lawson is lifeless. Chosen because they are quirky and unfamiliar, even the paintings by familiar names—Gifford Beal, Thomas Hart Benton, Arthur B. Davies, William Glackens, Man Ray, Theodore Roszak and Marguerite Zorach—are likely to head right back into storage once this exhibit is dismantled. All figurative—portraits, landscape, still lifes—they may be well-executed, but that's about it.

Sheeler's "Interior" |

Perhaps the most rewarding gallery is allocated to artists that Whitney collected in depth. Here, Stuart Davis merits his own wall, with modern but fairly traditional landscapes of New Mexico and Paris hanging side by side with "Egg Beater No. 1," the first in his famous series of that kitchen tool, an electric fan and rubber glove. Rendered in flat, interlocking geometric planes of green, brown and peach colors, it was a breakthrough that led Davis to additional innovations.

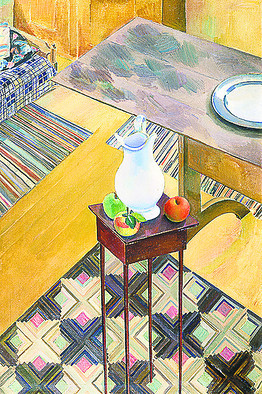

Precisionist Charles Sheeler, who received a rent-free apartment for 18 months from Whitney, also gets four works. His familiar, photographic "River Rouge Plant" hangs near "Geranium," an off-kilter still life that, uncharacteristically for Sheeler, contains nature, but which still plays with shapes, and "Interior," another, more geometric still life that capitalizes on his interest in patterned textiles.

The curators did not set up this exhibition as a contest between realism and modernism, but that's what it becomes, amply demonstrating that a static art world is far less interesting than a dynamic one. But if Whitney's democratic purchasing policy didn't work to the museum's ultimate advantage, neither would following the market have. In 1930, for example, she purchased "Mrs. Gamley," a forgettable portrait by Luks, for $8,000. The same year, she bought Hopper's masterpiece "Early Sunday Morning" for just $2,000 and Demuth's iconic "My Egypt" for $1,500. In the end, there is no substitute for a discriminating eye.