Public pension funds, union pension funds, religious investors, hedge funds—all have forced their way into the corporate governance process in recent years. Could there possibly be any other constituency in the shareholder universe that wants to have its say at the annual meeting and in the boardroom?

Yes, indeed. The foundation world is beginning to file shareholder resolutions, write letters to management, comment on policy proposals with the Securities and Exchange Commission, and, in at least a couple of cases, give a fellow nonprofit organization money to buy significant stakes in a company so that it can push for a change in policy.

Courtesy Corporate Board Member |

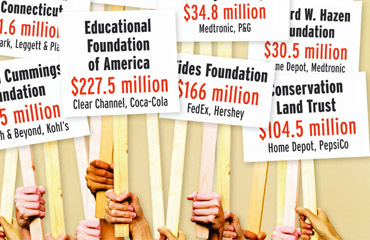

While individual foundations have nowhere near the financial heft of, say, the big California pension fund Calpers, their number and the money they control as a group are impressive. In 2005 the Foundation Center counted over 71,000 grantmaking foundations in the U.S. and pegged their assets at $550.6 billion—both figures more than double what they had been 10 years earlier. Since then those assets have probably grown to more than $600 billion, according to Doug Bauer, senior vice president of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, a firm that started as a service to the Rockefeller family and now also serves other clients. Bauer figures that between 40% and 50% of that sum is invested in common stocks.

And in this age of competitive philanthropy, there's more investment power in the pipeline. Multibillion-dollar gifts by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, plus frequent entreaties from celebrities like Bill Clinton and Bono, are goading scores of high-net-worth individuals to establish their own foundations. Giving by Americans totaled close to $300 billion in 2006, and while much of that went directly to religious groups or education, other donors used their money to endow intermediary foundations, bodies that invest the money and parcel it out over time to selected causes.

With the ranks and fortunes of wealthy individuals growing—it took a net worth of $1.3 billion to make the Forbes 400 list of the richest Americans in 2007, up from $1 billion the previous year—and barring a market catastrophe, experts expect the growth in giving to increase.

In tight proxy contests, such as governance, environmental, and social-issue resolutions that attract the support of more than 40% of investors, a swing by foundations from management's side to the activists' column could make a big difference. And while activist foundations have been more exercised about social issues than questions of governance, they do tend to vote along the same lines as public pension funds, union funds, and other shareholder advocates on such things as majority voting and declassifying boards. "I hope we add power and strength to that movement," says Victor De Luca, president of the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation, a 60-year-old organization whose interests center on the environment, agriculture, and reproductive rights. It has about $62 million in assets.

In some ways, it's a wonder the foundations took so long to wake up to their voting power. The Council of Institutional Investors, established to push for shareholder rights, is more than 20 years old, yet just two foundations are members: the Lens Foundation for Corporate Excellence, founded by veteran shareholder activist Robert A. G. Monks specifically to promote corporate responsibility, and the Nathan Cummings Foundation, which is funded from the estate of the founder of the company now known as Sara Lee Corp. and has some $575 million in assets. "Other folks have been out front on these issues for many years," Bauer allows, "and we [the foundations] have been playing a catch-up game."

Foundation activism has its roots in the social movements of the 1970s and 1980s, when many foundations took stands on moral issues, siding with those who protested the apartheid regime in South Africa, for example. Some began to divest or avoid investments in companies that had problematic geographical ties—with Libya, say—or products, such as cigarettes. Then came the news, in 1994, that Intel Corp. was expanding its semiconductor plant in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. The Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation, which owned 100 shares of the company, then worth about $3,000, was not happy with a planned water diversion that the expansion entailed or with the chemicals that would be used. It believed New Mexico had weakened state environmental regulations as a way to attract Intel. Stephen Viederman, then president of the foundation, protested the plant expansion at Intel's annual meeting. His appearance was noted by Timothy H. Smith, who at the time was executive director of the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility. Smith said in an article in the New York Times that it was the first time a foundation executive had directly confronted corporate management. "Noyes is on the cutting edge of a new trend," he added.

Intel declined to modify its plans for the expansion, according to De Luca, Viederman's successor, but did agree to be more sensitive to the concerns of local communities in the future. Perhaps more important, Viederman's protest "sent a message to the community of foundations that corporations could be questioned on these kinds of issues," De Luca says.

Nowadays the Noyes Foundation uses the whole panoply of shareholder-activist tactics. During the 2007 proxy season, it voted in support of dissidents on each of the 31 shareholder resolutions filed at 18 targeted companies where it was invested—among them Bank of New York, Blockbuster, and Citigroup. It backed demands for declassifying boards, providing more detailed reports on political and charitable contributions, separating the jobs of chairman and CEO, limiting executive pay, and so on.

De Luca has also chosen boardroom diversity as a key issue. In 2007 the foundation withheld votes for directors at 71 of the 216 companies in its portfolio, because women were lacking on their boards. The targets included Boston Beer Co., Marvel Entertainment, and Pinnacle Entertainment, a casino outfit. De Luca wrote letters to each company to "urge the board of directors to address this issue by taking steps to recruit and identify qualified women for the company's board during the next nomination cycle." The result? By September, De Luca says, he had received responses from 10 companies, "most of which said they will consider our request."

De Luca's closest companion as an activist is Lance E. Lindblom, president and CEO of the Nathan Cummings Foundation, which uses its assets to advance "democratic values and social justice, including fairness, diversity, and community," according to its mission statement. Lindblom sees foundation activism on the rise in the fact that "I get more and more invitations to speak about it." These have included talks at Harvard Law School's program on corporate governance, the National Center for Family Philanthropy, and the Native American Finance Officers Association.

Lindblom woke up to activism in 2002 after the board decided that the foundation should take a more vigorous role as an investor. Like other activist foundations, Nathan Cummings saw that it might be sitting on both sides of a fence, with groups it was helping to support going after companies where it was invested. For instance, the foundation had been giving grants to various organizations that were working on farm-policy issues, such as pollution caused by hog farms. Says Lindblom: "I realized that we owned a significant amount of Smithfield Foods," one of the offenders. In 2003 he joined with the Sierra Club and Amalgamated Bank in a resolution asking Smithfield to report on the environmental impacts of its operations. The resolution never made that year's proxy statement, but it did in 2004, 2005, and 2006, by which time 30% of the shareholders backed it. Smithfield, where Nathan Cummings is still invested, has "greatly enhanced" its reporting, the foundation says.

Since 2003, Nathan Cummings has filed or co-filed 37 resolutions at 21 companies—including 10 resolutions in 2007 at as many outfits, among them ConocoPhillips, homebuilders Centex and D.R. Horton, supermarket chain Kroger, and Ultra Petroleum.

The foundation now also has a full-time director of shareholder activities, Laura Shaffer, a former financial adviser with a master's from the London School of Economics who focuses mainly on the effects of climate change and political contributions on long-term shareholder value.

The outcomes of these resolutions vary, of course, as they do for those filed by other kinds of shareholder activists. Some have been withdrawn after the companies responded: D.R. Horton, for example, agreed to write reports about its efforts to make homes more energy-efficient. Some resolutions have gone to a shareholder vote. About 12% of the votes cast at ConocoPhillips, for example, backed a call for full disclosure of political contributions. Shaffer says the foundation's future activities will focus on what the oil and gas industry, retail companies, and homebuilders are doing about climate change.

It wasn't just Noyes and Nathan Cummings that catalyzed foundation activism. Three other forces have been at work: organized instigation, global warming, and the Los Angeles Times.

In late 2002, members of the Rockefeller family asked Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors to "figure out how foundations could influence corporations on social issues," says the firm's Doug Bauer. Looking around for someone to help him out with the assignment, he discovered the As You Sow Foundation in San Francisco, a group that describes itself as "dedicated to ensuring that corporations and other institutions act responsibly and in the long-term best interests of the environment and the human condition." Conrad MacKerron, director of its corporate-social-responsibility program, had been working on shareholder-activism campaigns and talking with corporate management on several issues—from recycling plastics and computers to testing genetically modified foods—since 1997.

Together the two new allies created Unlocking the Power of the Proxy, a 64-page how-to guide for would-be foundation trustees and staff members. Bauer says that about 11,500 copies have been distributed since then, either in printed form or by downloading. "We're educating a lot of people," he says. "People now understand that proxy voting is a key concern, and in parallel with that, mission-related investing has emerged." This coming proxy season the pair will update Proxy Season Preview, a report they brought out in early 2007 that summarized the previous year's proxy voting on a range of issues.

Meanwhile, interest in global warming was, so to speak, heating up. Concerned by shrinking polar ice caps, numerous powerful hurricanes, and U.S. energy policy, previously passive foundations discovered that they could use their investment power to influence corporate policy on climate control. Denis Hayes, president of the Seattle-based Bullitt Foundation, e-mailed several hundred environmental foundations during the 2007 proxy season, alerting them to global-warming proposals by shareholders at various companies and explaining how they could get involved. It's tough to measure how effective this blizzard was. Of the 43 climate-related proposals, 15 were withdrawn after the targeted companies took some positive action. Among the rest, an average 21.6% of shareholders backed the resolutions. At Allegheny Energy, 39.5% did, a record.

Foundations' involvement in the push for climate control can also be seen in their growing support of Ceres, a Boston-based coalition of environmental groups and investors. The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund have joined Ceres' Investor Network on Climate Risk. And last October, 25 foundations, including the Skoll, Surdna, and Winslow foundations, signed a demand put together by Ceres and the Investor Network on Climate Risk, calling on Congress to legislate stronger curbs on pollution that contributes to climate change, such as greenhouse-gas emissions.

As for the role played by the Los Angeles Times, last January the newspaper ran a two-part series of articles about the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Headlined "Dark Cloud Over Good Works of Gates Foundation" and "Money Clashes With Mission: The Gates Foundation Invests Heavily in Subprime Lenders and Other Businesses That Undercut Its Good Works," the articles outlined contradictions between the foundation's goals and its investing practices.

That split, the same dichotomy Lindblom had seen at Nathan Cummings, was no surprise to many foundation executives. "There is a firewall between the investing side and the program side in foundations," says the Noyes Foundation's Victor De Luca. "That's how they were set up." Normally, he explains, the investment side simply wants to make as much money as possible, while program officers want, at a minimum, to avoid conflicts with their programs—but know little about investing and shrink from advising on it. Research done by Doug Bauer at Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors in 2003 found that some 90% of foundations said they did not align their investments with their missions.

This may be changing. "We've had calls saying, 'We don't want to be in that position,'" Bauer says. "You can't do one thing with grants and one thing with investments."

De Luca is not so sure. "There's been some rethinking," he says, but "I believe that more foundations are looking at being an engaged shareholder through proxy voting." There's no doubt about the very aggressive course he has mapped for Noyes. Every year, he says, "I send a letter to our grantees that includes the following: If shareholder activism is or will be part of your organizing strategy, the foundation is open to a funding request to enable your organization to own the minimum shares necessary to participate."

One of what De Luca calls "the handful" that have taken up the offer is the Cornucopia Institute, a Wisconsin group dedicated to "economic justice for the family-scale farming community" and intent on preserving the cachet of organic farming. "We gave them $2,000 to buy stock in Dean Foods," De Luca says.

Stake in hand, Cornucopia has been prodding Dean's management. It has filed complaints with the U.S. Department of Agriculture asking for an investigation into alleged violations of organic regulations on Dean farms. At the last annual meeting, Mark Kastel, Cornucopia's co-founder, rebuked Dean Foods CEO Gregg Engles for letting reliance on big farms dilute the image of organic milk.

Of course, one risk faced by foundation activists is that their financial might may dwindle when the foundation gets caught up in a cause. The Gates Foundation dodged that eventuality. After the Times articles appeared, Patty Stonesifer, the foundation's chief executive, wrote to the paper to say that "changes in our investment practices would have little or no impact" on the suffering identified in the report. In other words, its investment and grantmaking arms will continue to operate independently.